- Rig Count Downturn Moves Into Uncharted Territory

- Dallas Fed: Houston’s Energy Sector A “Definite Liability”

- Buffett: Major Mistake Buying Oil Company At The Top

- Technology Helps Surplus Equipment Market Globally

- Demand Forecasts Down As OPEC Considers Quota Cut

Note: Musings from the Oil Patch reflects an eclectic collection of stories and analyses dealing with issues and developments within the energy industry that I feel have potentially significant implications for executives operating oilfield service companies. The newsletter currently anticipates a semi-monthly publishing schedule, but periodically the event and news flow may dictate a more frequent schedule. As always, I welcome your comments and observations. Allen Brooks

Rig Count Downturn Moves Into Uncharted Territory (Top)

As Mark Twain said, “History seldom repeats, but it often rhymes.” That philosophy has led investors and analysts to track the progression of the current rig downturn against prior ones in an attempt to gauge just how far the rig count still might have to fall before hitting bottom. Many analysts suggested that the current decline would more likely mirror the rig downturns of 2001-2002 or 1998-1999. Those industry downturns are within the business memories of many of the Wall Street analysts and some company executives, but we have been suggesting that the correction might more closely resemble the debacle that followed the industry boom of the 1970s. Even that model, however, may not prove an accurate guide for forecasting the bottom, or definitely how quickly we get there, this time.

The primary difference between past industry downturns and the current one is the existence of a global credit crisis in conjunction with a worldwide recession. There were credit market problems in 1997-1999, but they were primarily regional and associated with foreign currency problems that impacted certain countries in Southeast Asia. The collapse of the value of a handful of Asian currencies as their economies imploded due to the bursting of speculative property bubbles disrupted global trade and curtailed consumption. This economic contraction happened just after a decision by OPEC to boost its production to satisfy the growing oil thirst of these boom economies. The resulting supply glut depressed oil prices until global oil-supplying nations joined together and agreed to curtail production to bring supply and demand back into balance.

The 2001-2002 correction, on the other hand, was driven initially by the collapse of the technology company-driven stock market of the late 1990s. The September 11th attacks on the United States by al-Qaeda further contributed to the downturn. The economic recession was driven by the destruction of consumer and corporate wealth due to the stock market collapse and an increased fear that political stability worldwide was at risk of imploding.

Exhibit 1. 1997-1999 Decline Lasted For 84 Weeks

Source: Baker Hughes, PPHB

The different causes for these recessions were matched by oil industry experiences during the 1997-1999 and 2001-2002 downturns. The 2001-2002 correction was considerably shorter lasting only 38 weeks and less severe as the industry dropped 455 working rigs, or 35% of the beginning working rig fleet. In contrast, the 1997-1999 rig market decline needed 84 weeks to eventually reach bottom with the industry shedding 544 working rigs, or nearly 53% of its starting working rig fleet. So far, this rig market correction has lasted 26 weeks, but is continuing and we have lost 905 rigs, or 45% of the peak working rig fleet. At the moment, this rig downturn in terms of the number of working rigs lost is worse than either of the other two rig market corrections, and it has accomplished its damage in considerably less time than the earlier periods. This current rig downturn reminds us of the collapse of energy stocks last fall.

How does this current downturn compare with the 1980s correction? That earlier downturn actually was an extended market correction with intermittent periods of market improvement until the ultimate bottom was reached following the collapse in global crude oil prices in late 1986. The initial rig market correction of 1981-1983 was associated with the recession engineered by the Reagan administration through a tightening of monetary policy to break the inflation that had been raging within the U.S. economy during the latter half of the 1970s. Following that recession, the economy

Exhibit 2. Current Downturn Exceeds 2001 Rig Drop

Source: Baker Hughes, PPHB

began to expand and U.S. government policy regarding leasing of acreage in the Gulf of Mexico was changed. Those conditions contributed to a brief recovery in drilling activity, which was eventually undercut by the growing glut of oil and the battle between Saudi Arabia and other OPEC member states over OPEC’s share of the global oil market.

When the industry first turned down in 1981, global oil prices were in the $39 a barrel range as a result of inflationary forces and the fallout from the Iranian revolution and the removal of Iran’s oil from the global market. By the time the domestic rig count peaked at the end of 1981 at 4,530 working rigs, U.S. refiner acquisition cost of imported oil averaged about $36, down from $39 at the start of the year. By the time the initial rig count decline bottomed out at 1,807 rigs in spring of 1983, oil prices had only fallen to about $28 a barrel. Oil prices then started to rise, eventually getting back to about $29 a barrel as a recovering economy tightened the global oil supply/demand balance. In late spring of 1983, the U.S. government altered its policy for leasing acreage in the Gulf of Mexico from requiring that all blocks to be auctioned needed to be nominated beforehand by at least two companies to area-wide leasing where oil companies could lease any block without any pre-nomination. This shift generated one of the largest Gulf of Mexico lease sales ever, and definitely the largest up until that time, as oil companies seized the opportunity to acquire prospective drilling acreage, which resulted in more offshore drilling rigs eventually returning to work.

However, the damage to oil market fundamentals from high oil prices earlier in the 1970s began to surface as global oil demand peaked in 1979 and then fell for four consecutive years through 1983. The cumulative decline was about 6.5 million barrels a day, or about 7.5% of 1979’s oil demand. At the same time, non-OPEC oil supplies were growing as Alaska, the North Sea and Mexican production surged. Along with Brazil, these new, growing oil supply basins added roughly 4 million barrels a day to global supply. In 1984, oil prices averaged $28-$29 a barrel, followed by about a two-dollar a barrel decline in 1985 and then a collapse in 1986. Saudi Arabia, the dominant source of oil in OPEC in the early 1980s, acted through unilateral production cuts to defend OPEC’s $33 a barrel target price, but then was forced by some cheating cartel members to try to hold the organization’s benchmark price at $27 a barrel.

By January 1986, the U.S. refiner acquisition price for imported oil averaged only $25 a barrel, which subsequently fell to $18 a barrel in February, $14 in March and averaged $13 for April and May. June saw oil prices slipping to the $12 a barrel level and then to $11 in July, which marked the bottom in the oil price decline. However, the financial damage done to the highly-levered domestic oil and oilfield service industries was acute. The U.S. petroleum industry landscape was littered with bankrupt companies, both producers and service companies, along with failed financial institutions and legions of unemployed workers. Residential neighborhoods throughout Oklahoma, Texas and Louisiana became ghost towns as these unemployed oil industry employees gave up on their homes and moved on in search of work elsewhere. Within roughly five years, the energy world had gone from one of the greatest industry booms of all time to one of its largest busts.

Exhibit 3. 1980s Rig Market Correction Was Extended

Source: Baker Hughes, PPHB

Let’s look at the 1980s rig count record for possible guidance to the magnitude and duration of the current drilling industry downturn.

In the first leg of that drilling industry downturn, the rig count fell by 2,723 rigs, or about 60% of the industry peak count of 4,530 working rigs at the very end of 1981. This rig decline lasted for 65 weeks from peak to trough. Some analysts might say that because the rig count bounced up in the last few weeks of 1982, that this decline was over and we should be measuring a new rig drop period. We believe that the industry conditions in late 1982 were not materially improved from the earlier months of that year, nor the following year, and that is why the rig count decline quickly resumed.

Much like a stock trading between support and resistance price points, the rig count over the next several years essentially traded within a range bounded by that late 1982 recovery peak and the bottom of the decline in spring 1983. Then in 1986, the bottom fell out of the rig count along with crude oil prices. By that point the financial health of the global petroleum industry had been eviscerated and the drilling industry was essentially entirely bankrupt.

We have taken the pattern of this extended 1980s rig downturn and applied it to the current rig decline to see where we might wind up if that earlier cycle were to be followed. It suggests that while we have already surpassed the bottom of the first phase of the 1980s’ cycle downturn, from the 1,126 working rigs at March 13th we could see the industry needing to shut down another 211 rigs. Added to the current 905 rig decline, the domestic rig count would fall by 1,116 rigs or a 55% decline from the September peak of 2,031 working rigs.

Exhibit 4. Fewer Rigs In The Future If 1980s Pattern Holds

Source: Baker Hughes, PPHB

The complete 1980s rig cycle spanned 246 weeks from peak to trough. At the average rate the rig count is dropping, we would reach the comparable 1980s correction low in another eight weeks, or by May 1st. If achieved, the low would have been reached in 40% of the time of the 1997-1999 cycle, five weeks short of the entire 2001-2002 cycle and in 13% of the time of the 1980s cycle. The speed of this cycle’s decent, assuming that was the bottom, is astounding. It suggests that other factors are at work in the oil and gas business than merely commodity prices and the recessionary impact on oil and gas demand. We would suggest that the industry variable analysts and corporate executives have underestimated is the workings of the global credit crisis on business spending and confidence. While these concerns have been most visible in their impact on the U.S. drilling rig count, we thought it also would be interesting to examine the history of the international rig count for guidance about its movements in light of economic recessions and the credit crisis.

The international drilling market has tended to demonstrate much less volatility over time compared to the U.S. rig count as the work is primarily driven by large oil companies – both independent companies and national oil companies – and involves larger fields than those found in the United States. These characteristics have meant that the international drilling market has been slower on the uptake during commodity price rises and likewise slower to fall during price contractions. This pattern is clearly demonstrated when one compares the international (non-U.S. and Canada) rig count over time and the world oil price.

Exhibit 5. International Rig Count Moves With Oil Prices

Source: Baker Hughes, EIA, PPHB

The greater stability of the international rig count compared to the U.S. rig count is demonstrated by plotting the two measures over time. The volatility difference can be noted by examining the pattern of rig count movements during two corrections – 1981-1983 and 1997-1999. In the first case, the U.S. count peaked at the end of 1981 and bottomed in the spring of 1983 with a 60% drop. The international rig count did not peak until November 1982 and then bottomed in July 1984. These peaks and troughs were approximately one year later than for the U.S. rig count. Over its cycle, the international rig count only fell by 20%.

The pattern of the 1997-1999 rig market downturn was somewhat different than that of the 1980s, as the peak in drilling for both regions came at about the exact same time – September 1997 for the U.S. count and July for the international rig count. The bottoms for the two rig counts were within months of each other with the U.S. rig count touching bottom in April 1999 as the international count continued falling until reaching bottom in August 1999. The magnitude of the declines was measurably different – the U.S. count fell by 53% as the international count was only off 33%. Surprisingly, at the bottom of the 1999 rig market correction there were more rigs working internationally than in the United States – 556 rigs versus 488 – although at their respective peaks the U.S. had 206 more rigs working – 1,032 versus 826.

Exhibit 6. U.S. Rig Count Is More Volatile Than International

Source: Baker Hughes, PPHB

The current rig market downturn has shown some similarities to the 1997 correction as both the U.S. and international rig counts peaked in the same month – September. However, the magnitude of the U.S. rig count fall has been dramatic. It fell by 788 active rigs, or 61%, from the peak to the end of February. In contrast, the international rig count has only dropped by 88 rigs, or 8%. One has to believe that there is risk of a further decline in the international rig count over the coming months if oil prices remain depressed – at least compared to their levels of the past two years – and show few signs of rising while the credit crisis continues to adversely impact capital availability for all segments of the global petroleum industry and thus their willingness and ability to fund drilling programs.

How much further the international rig count might fall is no less easy to project than forecasting the bottom for the U.S. rig count. If, as some forecasts are suggesting, the U.S. rig count falls to 850 rigs, then we would be returning to activity levels last experienced in the 2002-early 2003 period. If we assume the international rig count mirrors the U.S. count and retreats to that activity level, there is room for an additional approximately 275 rig drop from February’s 1,020 working rig count. While we cannot rule out a decline of this magnitude, our intuition suggests that it is too severe a correction.

We remain optimistic that the economic stimulus efforts of governments around the world, coupled with the long-term business strategies of large oil and gas companies will support petroleum industry capital spending at levels that will keep most of the current international rig fleet active. There is a significant difference between the health of the U.S. natural gas market, which is the focus for roughly 78% of the active drilling rigs, and that of the global oil market. Both markets suffer from oversupply and weak demand conditions, but in our view, the global oil market could return to a semblance of balance faster than the U.S. gas market. That difference is critical to our view that the damage to the U.S. oilfield market has been, and will continue to be, much greater than for the international oilfield market. We must always remember, though, that while the global oilfield market is composed of many smaller, regional markets, there is a certain spillover effect from one market into another. A global oil industry malaise is the greatest risk for oilfield company executives.

DallasFed: Houston’s Energy Sector A “Definite Liability” (Top)

In the latest Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas’ Beige Book dealing with business and financial trends in the 11th District of the Federal Reserve System, the slowing economic growth driver of oil and gas markets was highlighted as a “definite liability” for Houston. The Dallas Fed’s conclusion became the headline for a story on the Houston Business Journal’s web site discussing the local economy and its growing economic problems. We were, admittedly, taken aback by the Dallas Fed’s conclusion, as we would have thought the headline more appropriate for a story about Houston in the 1980s and not today.

We know that Houston is known internationally as the “Energy Capital of the World” due to the concentration of headquarters for international oil companies and oilfield service companies. Houston has benefitted from the boom in oil and gas prices over the past four years, and is coming to grips with the energy industry’s reversal of fortune due to the collapse in commodity prices during the second half of 2008. Two economists speaking to a group of real estate people last week said that energy was responsible for 70% of Houston’s growth last year and that would be a negative this year. ConocoPhillips (COP-NYSE) earlier announced employee layoffs along with all three of the largest oilfield service companies headquartered here. But to term energy as a liability for the Houston economy seems a little bit too strong, at least for us. That is not to say that there aren’t cracks in the veneer of the energy industry, but until some new, non-hydrocarbon based energy source emerges to power global energy needs, oil and gas will remain the dominant energy source both for the U.S. and globally long into this century.

To examine the liability claim of the Dallas Fed, we looked at the latest local employment data, which unfortunately does not provide the extent of detail to really answer the question of how vulnerable Houston’s economy is to lower energy industry employment. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics provides monthly data for the Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown MSA (metropolitan statistical area) by broad industry category that enables us to gain some feel for employment trends. The data we gathered covered the 24-month period spanning 2007 and 2008. The data shows that the proxy industry for energy employment did increase its share of the Houston regional employment, but the increase was small and does not appear to present the economic risk suggested by the Dallas Fed.

From January 2007 through December 2008, Houston employment, measured from the establishment data of the employment statistics, grew by 194,500 jobs to 2.67 million. That was a 7.9% increase. The proxy for the energy industry is the employment category Natural resources and mining, and during the period it grew by 13.0% or 10,700. As a share of the total Houston MSA’s employment, this sector rose from 3.3% to 3.5% over the 24-month period. A significantly larger employment category, Education and health services, grew by 8.5%, or 23,200 employees over the same period. As we know, Houston has a number of fine universities and a world renowned medical center, which have been significant drivers of Houston economic growth for many years.

Exhibit 7. Energy Is Not The Dominant Employer In Houston

Source: BLS, PPHB

The largest employment categories in Houston are Trade, transportation and utilities with 552,800 employees at December 2008, followed by Profession and business services with 399,700 and government with 369,800. Even if we doubled the Natural resource and mining employment (93,300), it would still pale in comparison to these other categories, especially government. For this reason we question the Dallas Fed’s statement.

In understanding the role of energy in Houston, we often think about the downtown office buildings that housed many of the famous oil companies – Continental Oil, Texaco, Humble Oil, Gulf and Pennzoil, to name a few. What we also remember was that during the 1970s the city became the center of the global oil industry boom, only to have that image tarnished by the industry bust of the mid 1980s. After years of Houston being a Mecca for energy industry jobs – all the Rust Belt states lost population to the Sun Belt states throughout the 1970s U.S. recessionary period – the city suffered significant economic pain with the oil price collapse of 1986. But from that depression, which left many neighborhoods looking like wild west ghost towns with tumbleweed rolling through, the city of Houston rebounded through increased emphasis put on expanding its other industries, especially the health and education businesses.

A City of Houston Planning and Development document authored in 2000, and subsequently updated, made a number of points about the then recent growth and diversification of the Houston economy. In 1981, energy related industries accounted for 84.3% of Houston’s economic base. By 1989 that percentage had declined to 61% and by 2002 it had fallen to 48.3%. According to the Planning and Development report, that energy-related industrial base was comprised of 32.6% upstream oriented businesses and 15.7% downstream focused. While we haven’t seen any recent figures, we doubt that there has been a wholesale increase in the dependency of the Houston economy on oil and gas. In fact, the global impact of China and other low-cost labor markets on the U.S. manufacturing sector has also been felt by the energy industry in Houston. Many of us remember when driving west from downtown on the Katy Freeway in the 1970s and passing the 610 interchange that on the right were the plants of Cameron Iron Works (now known as Cameron International after various transitions) with their huge flaming furnaces producing valves and other large iron pieces used in making oilfield products. We have other memories of driving down Navigation Boulevard past the Hughes Tool, Reed Tool and Baker Oil Tool plants, to name a few, that were humming with activity. Most of this manufacturing base has been scattered to low-cost labor markets both here and abroad. That transition occurred over the past 20 years.

While there may be a lot fewer drilling rigs being used by the energy industry today, there haven’t been a large number drilling in the Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown region for many years. So while there are a number of drilling contractors headquartered in Houston, most of them are staffed with management people less impacted by the fluctuations of the rig count.

Houston’s energy industry does have a vulnerability, but it’s not $40 a barrel oil and $4 a Mcf natural gas. It is plug-in automobiles that can run for hundreds of miles on one charge, powered by low-cost, long-lived batteries. That’s when you are talking about change that will alter Houston’s energy franchise. But just as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the capital of the U.S. whaling industry, didn’t die immediately after kerosene and rock oil were introduced into the illumination fuel mix, neither will the oil and gas business die overnight with the introduction of battery-powered automobiles, either. However, the question oil industry executives should be pondering is whether there are, or will be, opportunities for them in the energy business of the last half of this decade. Houston has always been populated by risk-oriented entrepreneurs so we remain confident about the long-term health of this city. But energy as a “definite liability” seems a bit too harsh a characterization of Houston in 2009.

Buffett: Major Mistake Buying Oil Company At The Top (Top)

In his recent letter to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (BRK-A-NYSE) Chairman Warren Buffett outlined his poor performance in the face of a challenging economic and financial environment that resulted in a decrease in the firm’s net worth of $11.5 billion, the worst performance in the 44-year history of the company. Mr. Buffett admitted to “a major mistake of commission” in buying a large amount of ConocoPhillips (COP-NYSE) stock when oil and gas prices were near their peak. He goes on to say, “I in no way anticipated the dramatic fall in energy prices that occurred in the last half of the year. I still believe the odds are good that oil sells far higher in the future than the current $40-$50 price. But so far I have been dead wrong. Even if prices should rise, moreover, the terrible timing of my purchase has cost Berkshire several billion dollars.” Maybe Mr. Buffett can be excused for falling for the siren song of $200-$300 a barrel oil prices that drove energy stocks last year, but in reality he merely bought the wrong company.

In previous years, COP purchased several companies as a way to enhance its production and reserve growth and to position itself for faster growth in the future. Unfortunately, it too bought when commodity prices were high, but for several years, just like home prices, bad purchases were bailed out by rising prices. When the music stopped in early July 2008, COP was left looking for a seat like virtually every other oil and gas company.

COP management recently met with Wall Street oil analysts and told them they don’t see an economic recovery until sometime in 2010; that the company will stay with its lower projected capital spending of $12.5 billion, down from $19 billion, of which $10.3 billion will be targeted for upstream projects; that it is cutting 1,300 jobs (4% of its employees) and hopes to save $1.4 billion in annual costs; that its production should be flat at 1.8 million barrels of oil equivalent; and that it expects its reserve replacement to be at least 100% for each of the next five years. While a solid outlook in the face of the global oil industry and the commodity price collapse of last year, COP

Exhibit 8. Solid E&P Performance

Source: PLS

doesn’t look quite as solid as ExxonMobil (XOM-NYSE), which is boosting capital spending; expects to grow production by 2.5% this year; and reported 110% reserve replacement (excluding asset sales) last year. Over 2004-2007, XOM has added more reserves than its three largest global competitors and did so at a lower cost. In addition, XOM has generated much greater shareholder returns over the past 5-, 10- and 20-year periods in the stock market and any of its competitors and the market in general.

The mistake Mr. Buffett made was not just buying an oil company when oil prices were high, but failing to understand that the reason XOM shares always appeared to be expensive is that they run a highly disciplined company that understands it is virtually impossible for the oil industry to out-earn other industries over an entire oil industry cycle. Therefore, an oil company with a long-term investment strategy needs to be cautious when investing and seek to gain technological and cost advantages in regions where it operates. XOM management has done an excellent job in guiding the company through many price cycles, and its investment discipline has produced the outstanding financial results. The recent announcement that its January oil discovery offshore Brazil could contain upwards of eight billion barrels of reserves, or as much oil as the country’s heralded discovery, Tupi, the largest discovery in the Western Hemisphere in three decades, is another example of XOM’s successful investment focus.

Exhibit 9. COP Hurt By Falling Commodity Prices Like Others

Source: Yahoo Finance

When we look at stock price charts for both COP and XOM, one can see that Mr. Buffett purchased his shares (his average cost is $82.55) largely during the last half of 2007. Had he bought XOM instead, he would still have lost money. However, given XOM’s returns to shareholders compared to its capital spending and relative to its competitors on this measure, I think Mr. Buffett might be less critical of his investment timing mistake.

Exhibit 10. XOM Down: Still Generates Attractive Returns

Source: Yahoo Finance

Exhibit 11. XOM Stars In Investment Returns To Shareholders

Source: PLS

Exhibit 12. ExxonMobil Returned More To Shareholders

Source: Financial Times, PPHB

What I do suspect is that the publicity Mr. Buffett has received for his COP investment could turn other investors off for investing in energy securities. In order to woo investors to commit funds to a capital intensive industry, companies may need to be thinking more about increasing their returns to shareholders, and especially in a more consistent manner. Dividends are likely to become a much more debated topic in energy company board rooms as the preferred way to return profits to shareholders.

Technology Helps Surplus Equipment Market Globally (Top)

We were on a panel at a conference recently discussing the outlook for the oilfield service business with the head of an intriguing company marrying internet technology with surplus oilfield equipment to help boost returns to its customers. Network International, headed by Boyd Heath, provides internet-based auctions for surplus oilfield equipment. With the downturn in oilfield activity due to lower oil and gas prices, the volume of surplus oilfield equipment is growing. The concept of internet auctions is relatively simple, but the results, as expounded on by Mr. Heath have been impressive, which is largely due to his firm’s ability to capitalize on technology to extend a local market into a global one.

Sellers have always known that having more buyers is always better than fewer buyers when trying to maximize sale values. Because oilfield equipment tends to be heavy and bulky, whenever it is sold at auction, buyers generally are forced to travel to the equipment. While we haven’t seen too many used oilfield equipment auctions in recent years as the industry instead has struggled to reactivate old equipment and build or buy new to meet demand, auctions may become a more active endeavor.

In an industry environment where operating costs are under strict scrutiny, understanding how much it actually costs to hold on to surplus equipment is receiving greater attention from company managements. Mr. Heath presented a chart showing that when all costs associated with holding surplus oilfield equipment are considered, the total can approach as much as 20% of the asset’s value. This cost estimate does not take into consideration the owner’s cost of capital, which further increases the financial cost of surplus equipment. Additionally, the cost analysis doesn’t consider the possible financial impact of an item’s obsolescence. The idea that a company, during the next upturn, wants to promote the idea that it uses “old technology” because it has it in inventory rings hollow. All companies wish to be perceived as being on the “leading-edge” of technological employment. Therefore, shedding assets now that currently have value that might decline in the future due to obsolescence becomes another selling motivator.

In the past, oilfield equipment auction outfits tried to round up as much used equipment as possible and locate it in one spot in order to entice more buyers to travel to the site. Technology may begin to

Exhibit 13. Surplus Equipment A Meaningful Cost For Owners

Source: Network International

change that pattern. One positive for the used oilfield equipment market is that almost all the items utilized must meet certain American Petroleum Institute (API) standards. With this certification, the issue then becomes the condition of the items and the volume of them in determining the price for used equipment. With digital cameras and video recorders, people can provide quality photos of used equipment for people to assess without having to actually travel to the auction-site to “touch” the items.

Among the greatest challenges for oilfield auction firms is enticing the maximum number of buyers to show up to the sale thus insuring that items being sold receive top dollar bids. However, if you can expand the geographic market of the sale from the local area to a national or eventually a global scale, the number of potential bidders should grow exponentially. Mr. Heath presented the results from one of his firm’s recent auctions in which the online bidding generated a greater number of bids from more and different buyers located around the world. The additional bidders helped to double the transaction price. The seller had to be very happy. So was Network International as it earned a higher fee. Surprisingly, Network International earned additional income when a prior sale client who had declined to pay a previous invoice paid up in order to be able to bid in this auction. They were not successful in their bid.

We would not be surprised if 10-15 years from now, people question how the oilfield industry ever handled surplus equipment without web auctions, much as today we wonder how business functioned before faxes, cell phones, Blackberries and email. Technology such as web auctions is a step forward in improving economic returns for companies in the energy industry.

Exhibit 14. Web-based Auctions Improve Equipment Prices

Source: Network International

Demand Forecasts Down As OPEC Considers Quota Cut (Top)

Last week marked the release of revised oil market forecasts by all three of the primary energy monitoring organizations – the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Energy Information Administration (EIA) and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Each of the organizations reduced its estimate for 2009 global oil demand from its earlier forecast. Moreover, as a result of the global credit crisis that exploded on the scene last September, it is possible these forecast reductions are not over.

The financial crisis caused credit markets globally to cease functioning bringing international trade to a standstill. With reduced trade and consumers under tremendous financial stress causing them to stop spending, companies cut back their production to help bring inventories under control. Companies also cut back capital spending and laid off employees enmasse who were no longer needed given lower output. More unemployed workers put further downward pressure on consumer spending and contributed to additional home mortgage market problems. As the problems associated with the credit crisis, consumer and capital spending cutbacks and lower manufacturing output in the United States spread globally, forecasts for worldwide economic growth in 2009 were revised sharply lower by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the United Nations (UN). These lower growth outlooks suggest less energy will be needed this year. Exactly how much less energy will be needed is what the forecasters are trying to get their arms around.

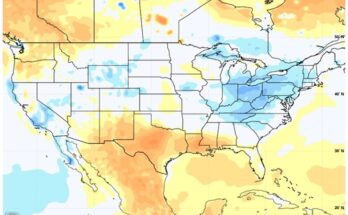

Exhibit 15. The IEA Has Been High In Its Demand Forecasts

Source: EIA, PPHB

We have been tracking the problems the IEA has had with its annual oil demand forecasts since the agency grossly underestimated demand in 2004. That miss was primarily associated with the agency’s faulty forecasting model for predicting China’s oil demand. However, since 2004, the IEA has tended to overestimate by a meaningful amount the following year’s oil demand estimate in its early in the year projections. As the year unfolds, the IEA finds itself in a constant revision mode, and almost always revising the estimate lower.

Exhibit 16. EIA’s Early Forecasts Have Also Been Too High

Source: EIA, PPHB

The EIA has suffered from the same forecasting problem as the IEA.

We have not done a study for the OPEC forecasts, but suspect that their models have tended to be off, too. These forecasting errors may be symptomatic of the challenges of forecasting, or they may reflect the problems of relying on other bureaucratic bodies for the underlying economic growth projections that drive these oil forecasting models. The IMF, World Bank and UN have little incentive for issuing critical forecasts of the future, or to issue frequent updates, since these bodies are dependent upon governments to provide the funding for their organizations.

Exhibit 17. OPEC Shows 2009 Forecast Trend

Source: OPEC

The implication of these forecasting challenges is contained in a chart from the March 2009 OPEC Monthly Oil Report issued last Friday. The chart shows the monthly revisions to OPEC’s global oil demand forecast beginning last fall through the current month. Given global economic and financial market conditions, one cannot rule out the possibility of further oil demand downward revisions. And therein lay the challenge for OPEC whose member country oil ministers were meeting on Sunday, March 15th to determine whether or not to reduce the cartel’s production quotas.

To date, the compliance of OPEC members to the last production quota reduction has been quite good, approaching 80%. Additionally, crude oil prices have strengthened in recent weeks but there are very mixed signals about current demand trends. If oil demand continues to fall, then any OPEC action that does not reduce current production will add to the global oil surplus and push prices lower. On the other hand, if the recent signs of improving demand are correct, then an OPEC decision to maintain current production levels will likely head off a spike in prices in the foreseeable future. Should OPEC cut production and demand begins to rise, then we could see an explosion in oil prices when the two trend lines cross.

Exhibit 18. OPEC’s Compliance With Its Production Cut

Source: Financial Times

Much was made last Thursday, when crude oil futures prices soared by 11% after having fallen the day before by 7%, about Russia attending last weekend’s OPEC meeting. Some analysts pointed to this event as a sign that Russia was going to cooperate with OPEC in a coordinated cut of global oil supplies. Thus they were interpreting the Russian news as a signal that crude oil prices were destined to rise in the near term. It should be noted that Russia did attend OPEC’s September meeting and no coordinated production cut was engineered then. Thus, we have a difficult time in believing that “this time is different.”

Russia may influence the outcome of the OPEC meeting but by playing a different role than people suspect. Saudi Arabia is the key to any further production cutbacks as it is the dominant source of crude oil in the cartel. The Kingdom also has substantial foreign exchange reserves that can allow it produce at a low price and not have its government expenditures impacted negatively. Saudi has further to go in its production cutbacks to help the organization attain 100% compliance. Critical to that happening, and for the organization to cut more if it feels it needs to, is a better understanding of the current state of the global crude oil market. The U.S. publishes its weekly inventory and demand numbers. Europe and Japan also provide fairly transparent oil market data through the IEA. China is the largest unknown market. Reports are that China has used the weak oil price environment to fill its four strategic storage facilities, and the next phase of its storage facility expansion is not finished being built. As a result, there are reports China is considering chartering tankers for additional storage.

Russia and China recently entered into a significant loan and oil supply agreement. The basis of the agreement addresses long-term supply needs for China with Russia getting the necessary funding it needs to improve and expand its oil industry. It is quite possible that Russia has the best current intelligence about China’s oil demand and supply needs. Keeping oil prices up is an important goal for Russia since its economy is highly dependent on oil export revenue. Therefore, Russia may be attending the OPEC meeting to provide information about China’s oil supply and demand requirements and its oil-buying interest level. Russia can play a role in lobbying the OPEC members on the appropriate actions to support oil prices. One step would be for the members to follow through on their production cuts, and even go beyond them if need be, although that step does not need to necessarily be announced to the world.

The real contribution from Russia beyond China’s oil market intelligence is helping OPEC understand what may be happening to Russia’s oil production and its export policies, since energy is now a critical part of Russia’s foreign policy. We view OPEC attendance as another confirmation that energy will be an important tool in Russia’s bag of foreign policy initiatives. $147 a barrel oil last year and Russian natural gas supply cutoffs to Europe the past two winters should be important signals that energy nationalism has entered a new phase, one U.S. administrations have not fully grasped. Energy nationalism could be a wild card in the global economic recovery over the coming years.

|

Contact PPHB: |

|

|

1900 St. James Place, Suite 125 |

|

|

Houston, Texas 77056 |

|

|

Main Tel: (713) 621-8100 |

|

|

Main Fax: (713) 621-8166 |

|

|

www.pphb.com |

|

|

Parks Paton Hoepfl & Brown is an independent investment banking firm providing financial advisory services, including merger and acquisition and capital raising assistance, exclusively to clients in the energy service industry. |

|