- With Crude At $80, It’s All About The Gas Market

- The Gas Shale Controversy Turns Ugly

- The Offshore Wind Saga Continues With Further Delay Likely

- How Significant Is Saudi Arabia’s Oil Pricing Move?

- Wall Street Says Energy Is Attractive Investment Sector

- Houston Energy Employment: Is The Worst Behind Us?

Musings From the Oil Patch

November 10, 2009

Allen Brooks

Managing Director

Note: Musings from the Oil Patch reflects an eclectic collection of stories and analyses dealing with issues and developments within the energy industry that I feel have potentially significant implications for executives operating oilfield service companies. The newsletter currently anticipates a semi-monthly publishing schedule, but periodically the event and news flow may dictate a more frequent schedule. As always, I welcome your comments and observations. Allen Brooks

With Crude At $80, It’s All About The Gas Market (Top)

It’s funny how many industry participants and energy company executives complain about the impact of “low” commodity prices on their financial returns and business activity. Oil prices collapsed but have now climbed back to a level that is more than half of the all-time peak of $147 a barrel experienced last July – all within a span of 15 months. In fact, the recovery in oil prices from their lows has occurred in a little more than 10 months. But while oil prices are doing better, it’s the domestic natural gas market that is the challenge now.

Exhibit 1. Oil Prices Have Recovered, Gas Prices Lag

Source: EIA, PPHB

Until recently, natural gas prices had dropped almost continuously throughout the year in contrast to the rise in oil prices. Based on various forecasts for the economy and natural gas production, we are starting to see a wide range of outlooks presented for the gas market. These outlooks range from a potentially explosive recovery in prices next year to a more pedestrian improvement in which producers will be financially challenged. As of yet, no one sees the gas market being worse next year. Given this wide diversity in forecasts, we thought we would take a look at the gas market from a 50,000-foot perspective.

The natural gas market has struggled with the continued sustainability of production in the face of a sharp drop in gas-oriented drilling. As the rig count collapsed during the fourth quarter of 2008 and through the first half of this year, expectations were high that gas production would start to fall, slowing the buildup of gas storage inventories for this winter and helping to boost gas prices. That view was predicated on the historical pattern of gas production falling and gas prices eventually rising following past slowdowns in gas-drilling as the industry’s production decline treadmill was considered to be pretty steep without new wells continually being poked and new supplies hooked up. What wasn’t understood well in this downturn was the role the highly productive gas-shale developments were having on the gas production picture.

The conventional view is that gas production will begin dropping by year-end as the extended pause in gas drilling takes its toll on the delivery of new conventional gas production and the rapid decline rates for gas shale wells begin to be felt. Recent Texas gas production data suggest that the pace of its decline is increasing. Much of Texas’ gas production is conventional at the present time. The one unknown is whether there have been involuntary gas well shut-ins due to a lack of storage space or pipeline capacity.

Exhibit 2. Texas Gas Shows Decline – Real or Involuntary?

Source: Texas Railroad Commission, PPHB

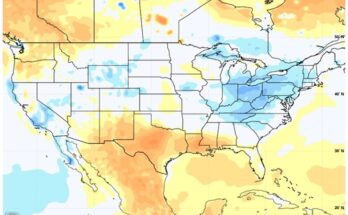

At the same time, there is a growing sense of optimism about the pace of the U.S. economic recovery and its impact on industrial and electric power generation gas needs. The electric power demand increase has been helped by the environmental push to reduce coal-fired power generation in favor of gas-powered sources. The ace-in-the-hole in this growing optimistic scenario is the expectation for a colder-than-normal winter that will eat through a substantial volume of the record supply of gas in storage. With falling inventories, rising economically-driven demand and clear signs of falling production, natural gas prices should rise to levels sufficient to stimulate an upturn in drilling.

An additional aspect to this recovery scenario is that the U.S. Congress, in an effort to demonstrate a pro-active effort in addressing climate issues, will embrace the use of compressed natural gas for vehicles and endorse the construction of more gas-fueled power plants. Of course both of these actions will require time and significant capital investment. With the belief growing that the nation now has 50-100 years of natural gas supply, due to the technical success in exploiting gas shales throughout the country, we should be able to use natural gas as a bridging fuel to our next source of energy and a cleaner economy. The risk, however, is that we commit to the capital investment program to support a greater role for natural gas in our energy mix only to find that it is not as readily, or cheaply available as currently believed. The statement by T. Boone Pickens that the gas supply will only last about 30 years would seem to undercut his efforts to motivate Congress to mandate increased use of natural gas as vehicle fuel, but maybe the statement was made while he was pushing his wind power projects.

As gas demand grows and readily available supplies contract, natural gas prices should climb to the $9-$10 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf) level, above the marginal cost for almost all significant gas producers. With oilfield service costs depressed due to the drilling downturn and excess service and equipment capacity, gas producers finding and developing (F&D) costs are also under reduced pressure. This will help the perceived economics of gas drilling, and we would fully expect the rig count to begin a sustained recovery. The problem could be with the pace at which oilfield service industry costs rise as many of the service companies need both higher activity levels and higher prices in order to return to acceptable levels of profitability. We doubt oilfield inflation will have much impact on producer F&D costs in 2010, but by 2011 the margin squeeze could be under way. But again we doubt that inflation in costs will increase at a fast enough rate to erode producer profitability in 2011, suggesting further that 2012 and 2013 could be years of reasonable activity levels and better energy industry profitability.

If we accept the above scenario as representative of the conventional view about the future shape and pace of the recovery of the natural gas market, what factors could cause it to be either better or worse? On the better side, the keys are probably the

Exhibit 3. Producers Need Higher Prices For Profits

Source: Art Berman presentation

shape of the domestic production curve along with the pace of the recovery in demand. It is quite possible we could see a sharp drop in natural gas production as the impact of the rapid declines from newly drilled gas-shale wells plays into the supply picture. Despite the debate over the economic ultimate recovery (EUR) of gas shale wells, both sides agree that these wells experience sharp declines in the early years of their productive lives. Two variables could influence the production profile – the number of drilled-but-uncompleted wells and the pace of re-fracturing of existing producing wells.

Exhibit 4. Gas Shale Wells Show Steep First Year Declines

Source: Art Berman presentation

As of this point, we have not spent much time digging into the data on wells drilled versus wells completed to try to answer the question of how many gas-shale wells remain to be completed and what the implication might be for gas production. We have seen two analyses by Wall Street analysts, looking at the same industry data, who come to dramatically different conclusions. One sees the number of uncompleted wells more in the 3,000 well range while the other believes the number could be as high as 11,000. One could drive a fleet of drilling rigs through that estimate range. All we do know with confidence is that there is a measurable number of wells in the drilled-but-uncompleted state, suggesting we have a ways to go before gas production might fall off the cliff.

With drilled-but-uncompleted wells sitting on the sidelines, and record gas volumes in storage, producers must deal with two significant anchors on natural gas prices. So with gas prices possibly capped in the $5-$6/Mcf range through the first part of 2010 and fewer gas hedges and only at modest premiums to current gas prices to help fund development activities, it is quite possible that producers start to run out of money in 2010. The current high level of fundraising by producers – selling stock, selling bonds, increasing bank lines and selling assets – suggests that the level of financial stress within the E&P sector is growing. It is also possible that auditors and reserve engineers could make tough calls on company financials and reserve valuations at year-end adding to the stress.

Capped gas prices and stressed financials, combined with a high number of uncompleted wells and a mild winter could provide the “kiss of death” for the E&P industry in the first half of 2010. On the other hand, a severe winter coupled with only a few uncompleted wells could produce a sharp spike in natural gas prices. While sharply higher prices and their positive impact on cash flows would be welcomed by producers and encourage them to step up their drilling, these higher gas prices potentially could play havoc with the pace of the domestic economic recovery and produce a government regulatory backlash.

Two other variables in the industry outlook are how much natural gas is the U.S. able to secure from Canada and the volume of liquefied natural gas (LNG) that flows into this country. For many years the U.S. has depended upon gas imports from Canada to bridge the gap between our domestic production and our consumption needs. The impact of low gas prices in North America and changes in the royalty picture in Alberta, Canada have significantly curtailed gas drilling north of the border, especially for shallow gas that brought forth smaller pools of supply but which could be done relatively quickly.

The LNG picture is different in that this industry is gradually evolving into a global commodity business. Many people feared a substantial increase in the flow of LNG into the U.S. this year, something that did not happen. The reasons for the shortfall in LNG volumes relative to expectations are that events such as another earthquake in Japan that shut down a nuclear power plant adding to gas demand and higher prices for LNG offered in Europe diverted supplies destined for the U.S. Additionally, the low North American gas prices made bringing LNG here less attractive. There was also a delay in the timing of the start up of several LNG export facilities reducing the anticipated volumes. But now that these facilities are up and running, or are about to start up, the global supply of LNG is expanding. That should put pressure on LNG prices, but as we have written in the Musings, there are substantial LNG volumes that could be loss-leaders for the project owners since all the project’s economics are covered by the extraction of highly valuable natural gas liquids (NGLs), especially in a world of $80/barrel crude oil. It is possible that significant volumes of LNG could come to the U.S. at very low gas prices and still reward the project’s owners while acting as a depressant on North American gas prices.

Exhibit 5. Lower 48 Gas Supply Not Responding To Rig Drop

Source: EIA, PPHB

Another variation (a bad one) on the conventional wisdom scenario is that gas production continues to grow as the drilling focus intensifies on the most productive areas within the gas shale basins and that there are a large number of drilled-but-uncompleted wells remaining to be brought on-stream. Since the newly drilled gas-shale wells all seem to have even greater initial production rates than the earlier wells in the same basins, the phenomenon of fewer wells producing more gas remains a stark reality. Even with a colder-than-normal winter in the Northeast region of the country, spring will arrive with significant gas volumes still in storage, which will depress gas prices throughout the spring and summer injection season next year. While the recovering economy continues to strengthen, it remains fragile and subject to risk from external shocks and additional financial challenges. The prospect of another round of housing industry problems coupled with a growing problem from commercial real estate loans means the economy could experience a “W-shaped” recovery pattern.

Exhibit 6. We Are In A Valley On Mortgage Loan Problems

Source: Agora Financial

A weak economy coupled with low natural gas prices could take a significant toll on the financial health of companies in the E&P sector. In an environment such as that, producers will be forced to cut back their drilling, which will contribute to a future gas price spike at some point, although maybe not soon enough to save some producers. On the other hand, to the extent gas producers act to maximize current production in order to generate greater cash flows from their operations, despite low prices, the expected decline in production from the drilling pause will be delayed helping to sustain downward pressure on gas prices.

At the end of the day, we continue to return to one key point we have made repeatedly in our articles on the natural gas market. The point is: Until we have a sustained recovery in the two economic sectors – housing and automobiles – that drive natural gas demand, it is going to be hard to expect a significant recovery in gas prices. Economists, analysts and politicians all point out how well those two industries are recovering, but even with the latest 11 million annualized unit sales rate for autos in October, you need to remember we used to average 16 million units. Today, we are running at about two-thirds of that historical rate and we don’t know how sustainable the current rate is. On housing, everyone seems to get excited about monthly new construction rates of 500,000-600,000 units when we used to build them at 2 million annual rates. These points are not to say that the economy isn’t getting better and that there won’t ever be an increase in natural gas demand, but we need to remember what the economic bubble that recently burst was doing to our perception of what was normal for the economy and the energy industry. Today, we are nowhere close to the bubble era “normal.” We are in the process of trying to figure out what our new “normal” will be.

At this point, our best guess about the domestic gas industry outlook is that the economic recovery continues, but with fits and starts. We expect the winter will be slightly colder than normal. Natural gas production will start to slide, but the enthusiasm of gas shale producers will mitigate the decline. Gas prices will remain range bound through the middle of 2010 in the $5-$6/Mcf range. The upper end of the price range may rise to $7/Mcf, but since we only expect about 2% annual growth in the U.S. economy next year, natural gas producers will be caught in the worst of all worlds. Prices will be high enough to keep people going and drilling. Gas prices will remain below the level producers need to become truly profitable. The production profiles, the demand growth prospects and lease termination pressures will combine with the belief that just over the horizon all things are much better making producers not only feel better but determined to hang on for that glory. As a result, we will remain mired in an era of substandard returns on capital in the E&P sector. The ultimate result may be that by the end of 2010 the E&P industry is in the midst of a major restructuring that will once again change the face of the industry.

The Gas Shale Controversy Turns Ugly (Top)

Last week was momentous for people involved in probing for an answer about the economic viability of gas shale development in this country. World Oil magazine senior management, in response to a complaint from a senior executive at Petrohawk Energy Corp. (HK-NYSE), a significant gas shale player and a company active in financial markets raising funds to continue that strategy, squashed Art Berman’s November column, causing him to resign, and later fired the magazine’s editor, Perry Fischer. In white collar criminal investigations, the police and prosecutors always say to “follow the money” as it usually provides a road map to the perpetrators. Today, so much of the gas-shale play seems to be all about money.

In our last Musings we wrote extensively about the gas shale play. We don’t claim to be smart enough to know who is correct in the EUR and IP debate, but Art Berman presented a cogent case backed by substantial data and analysis. Moreover, Art never claimed a corner on the “truth” but rather welcomed people to present contrary data, or show where his analysis was flawed. And based on his speaking schedule and meetings, Art was not trying to avoid critics.

We made two points about this debate in our Musings article. One was that we found the supporters, who seem reluctant to present data to counter the critical analysis, more inclined to resort to statements reminiscent of those of the Wall Streeters who defended the dot.com stocks during that investment debacle – full of hubris but with little substance. Second, we said that given the evolution of the debate, the onus was on the producers to present data to counter the research. Instead we got the “if you don’t like the message, shoot the messenger” response. This is a sad day for such a distinguished publication as World Oil.

The Offshore Wind Saga Continues With Further Delay Likely (Top)

In the last issue of the Musings we reported on the contract dispute between Deepwater Wind, the developer of the two wind farms destined for offshore Rhode Island, and the local electric utility, National Grid, over the price for the power produced. The contract negotiations had broken down due to Deepwater Wind asking for a price of 20¢ to 25¢ per kilowatt hour (kWh), while National Grid suggested the price tag, as calculated, was actually 30.7¢/kWh over the life of the 20-year contract. Deepwater Wind also had a provision in its proposal for a 3.5% annual escalation in the price of the electricity.

National Grid was comparing the contract price proposal against the estimated all-in cost for power it buys to supply the residents of Rhode Island of 9.2¢/kWh. Based on National Grid’s estimate, they would be paying more than three times the average price of the power they are buying now. Part of the explanation for the high price from Deepwater Wind was the per-unit cost for building and installing the six turbines in the demonstration project that will supply electricity to Block Island residents and surplus electricity to onshore residents − the subject of the contract negotiations. Deepwater Wind also argued that since this was the first offshore wind project in the U.S. the company was involved in a more challenging project than an onshore wind farm and thus it needed a higher return to offset the assumed risk. The final reason they gave for the higher cost was that there had been a surge in global wind turbine purchases pushing up the price of components.

With the contract negotiations ended, the pressure was put on the Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission (PUC) to either get involved as a facilitator or to push the two parties into arbitration. That decision needed to be made by early November to enable a contract to be completed by year-end for the PUC’s approval. One of the issues impacting the pricing dispute was the different interpretation by the two parties of the number of wind turbines allowed for the project. The original legislation authorizing the demonstration wind farm called for a 10-megawatt (MW) project size. As National Grid interpreted the law, the six s3.6 MW turbines would provide a nameplate capacity of 21.6 MW. However, National Grid assumed that the efficiency of the turbines was 40% – meaning that the wind would only blow with sufficient strength to generate electricity for 40% of any 24-hour time period. By applying a 40% efficiency ratio to the nameplate capacity (21.6 MW) it suggested an operating yield of 8.64 MW. Under National Grid’s interpretation, this would be the maximum number of turbines allowed as the seventh turbine would take the total effective capacity above 10 MW (8.64 + 1.44 = 10.08 MW).

The Rhode Island legislature completed a special session at the end of October during which it modified the wind farm law to specifically allow Deepwater Wind to install eight turbines. That should enable the company to reduce the cost of each of the units installed and thus negotiate a lower kWh-price. The legislature also modified the date by which the PUC must rule on the contract, pushing it back by a month to January 31, 2010. So while the electric power will still be more expensive than National Grid is currently paying for its other power, the difference should be less than the initial discussions suggested. So now Deepwater Wind and National Grid are back at the negotiating table, which should be a welcome development for residents of Block Island who are now paying 38.6¢/kWh for power.

But the good news in Rhode Island may be overshadowed by the latest twist in the battle to gain approval for the Cape Wind project for Nantucket Sound. With seemingly only a small number of minor hurdles left to clear, Cape Wind was surprised by the efforts of two Massachusetts Native American groups to claim all of Nantucket Sound as a cultural property to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This effort, supported by the main opposition groups to Cape Wind, could delay the approval of the wind farm project by upwards of another year.

The Aquinnah and Mashpee Wampanoag tribes say the 130 proposed wind turbines in Nantucket Sound would disturb their spiritual sun greetings and submerged ancestral burying grounds. The tribal leaders say their culture greets the sunrise each day, sometimes from sacred sites on the shore of Nantucket Sound, and this ritual requires unobstructed views. This has tied the tribes to the wind farm’s detractors’ original complaint that the turbines will detract from their view. According to Bettina Washington, tribal historic preservation officer for the Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe on Martha’s Vineyard, “We are known as The People Of The First Light. This is important to us.” Ms. Washington and George “Chuckie” Green of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe also said their ancestors hunted and walked upon the seabed in Nantucket Sound when it was dry land thousands of years ago. “Our people are buried there,” Mr. Green said.

During the last ice age, due to much of the earth’s water being retained in glaciers, New England’s coast line extended more than 75 miles farther from today’s shore. Previous archeological excavations in Nantucket Sound have found evidence of a submerged forest six feet under the mud, but no signs of Native American camps or other signs of human life.

Federally designated traditional properties tend to be defined areas, such as a boundary surrounding a ceremonial site, not an enormous body of water. That view was expressed earlier this summer in a letter sent to the Minerals Management Service (MMS) by Massachusetts Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs Ian Bowles and the state’s Secretary of Housing and Economic Development Gregory Bialecki. They urged the MMS to issue a favorable ruling on the Cape Wind project.

The MMS ruled in a 2008 draft environmental impact statement that only three historic properties would be affected by Cape Wind, but none were Wampanoag. Following a period of public comment, the MMS revised its position in its final environmental impact statement issued earlier this year. They determined that the project would adversely impact 28 historic property views and the “traditional religious and ceremonial practices” of the Aquinnah and Mashpee Wampanoag tribes. Normally, when adverse findings occur the interested parties work to develop an agreeable solution. But more puzzling is that the Aquinnah Wampanoag, while suddenly opposing Cape Wind, are proposing to erect wind turbines on tribal land already designated as a scenic landscape.

The MMS is federally required to consult with Massachusetts State Historic Preservation Officer Brona Simon. She must issue her opinion by mid-November. Earlier this year she criticized the federal government for failing to give sufficient consideration to tribal concerns. If she says Nantucket Sound is eligible for listing on the historic register, the National Park Service would have to resolve the dispute. Clearly that would add significant time to the Cape Wind approval process. But potentially more significant is that should the 560-square mile Nantucket Sound be listed, then other bodies of water around the country could be, too. That would make it potentially more difficult for other offshore wind farm projects to be undertaken, and also for the operation of other industries such as fishing and shipping.

Since Cape Wind is the first offshore wind project to be subject to federal government approval, the MMS is moving through the process slowly, making sure it is done in an environmentally and technically safe manner and with extensive consultation with local communities, industries and other governmental agencies. Even The New York Times editorial page at the beginning of November came out urging rejection of the tribal concerns and speedy approval of Cape Wind.

So while Energy Secretary Chu criticizes the domestic energy industry for failing to invest in clean energy technology, risking costing the U.S. its global leadership position, the governmental regulatory process and a small group of objectors are erecting roadblocks at every turn. NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) seems to be just as challenging an issue for clean energy as it has been for dirty power.

How Significant Is Saudi Arabia’s Oil Pricing Move? (Top)

Several days ago, Aramco, the state oil company of Saudi Arabia, announced that beginning January 1st of next year, it would change the way it priced its crude oil contracts. Aramco is switching from selling its oil at a discount to the price of the U.S.’s West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil, the historical benchmark price for global oil prices, to one based on an index of Gulf of Mexico sour crude oil prices published by Argus Media Ltd. The Argus Sour Crude Index (ASCI) is composed of a volume-weighted average of all deals done for three Gulf of Mexico sour crude oils. The three crudes are: Mars, Poseidon and Southern Green Canyon. The production volumes of these three crude oils have grown sufficiently large enough to facilitate active spot trading of cargos making the trading prices reflective of day-to-day conditions in the oil market.

These three sour crude oils currently are totaling about 1.2 million barrels per day (mmb/d) that should grow to 1.4 mmb/d next year. Based on the development plans for new deepwater oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico, these sour crude production volumes should climb to 1.9 mmb/d by 2013. So why is Saudi Arabia interested in shifting its oil pricing to the new ASCI measure and away from WTI? It reflects Saudi’s frustration with a number of economic and petroleum industry trends that have reduced the country’s ability to assure that it is realizing a fair price for its crude oil, the primary wealth of the Kingdom.

WTI is the benchmark against which all other crude oils are priced. The price differentials primarily reflect quality differences between the crudes and how easy or hard it is to refine them into various petroleum products. Because WTI is light and low in sulfur content, it is relatively easy to refine, especially into high value products such as gasoline and jet fuel. Heavier, sour crudes require a greater effort to refine and are seldom capable of producing the same percentage of high-value finished products.

Much of the crude oil produced in the central part of the United States is light, sweet crude that is either classified as WTI or is very close to it, quality-wise. Since that region of the country had a dominating influence on the development of the domestic oil business, WTI emerged as the crude oil price standard. In recent years, the United States has stepped up its imports of Canadian crude oil. As expanded pipeline capacity to move crude oil from Canada has come into service, the volume of oil flowing into the Cushing, Oklahoma transit point has grown, backing out the small volume of Gulf Coast crude oil that flowed north. This past summer, when oil storage facilities in the Cushing area filled up, WTI began to disconnect with the fundamental trends in the global crude oil market, and especially the Gulf Coast crude oil market. With so much of the nation’s refinery capacity located along the Gulf Coast and configured to process heavier and higher sulfur crude oils, which is more typical of the crude oils found offshore and imported, the pricing disparity, and especially the volatility in prices began to hurt the financial returns of oil exporters such as Saudi Arabia.

Today, Saudi sends about 1.5 mmb/d of its oil to the U.S. market, making it the second largest supplier behind Canada. Saudi does not trade its crude oil on the spot market, but rather enters into long-term contracts with buyers basing the price on a monthly calculation. The price is discounted by a certain percentage to reflect the quality difference from WTI and the cost of transportation. The price is calculated from the prior monthly average of WTI daily prices. The increased volatility of WTI prices has resulted in Saudi cargos arriving in the U.S. realizations that made them either marginally profitable or extremely valuable.

To understand the increased volatility in WTI pricing, one needs to only look at the spread between WTI and Brent, the North Sea oil benchmark. Historically, Brent has traded at a relatively stable discount of $1-$3 per barrel to WTI, which is demonstrated by the accompanying chart for the period from 2003 to 2007. Since then, the market has become increasingly more volatile, a trend that became almost violent during 2008 and early 2009. One of the drivers of this increased volatility was the recognition by investors that commodities was an acceptable, and even favored, investment diversification for large institutional pools of capital. One can see that there has been significant variability in the flow of funds into commodity ETF’s that represent investors playing commodity price movements. The belief is that commodity investing is losing its attractiveness.

Exhibit 7. Commodities Were In Favor

Source: Wall Street Journal

By shifting pricing to a new crude index that more closely reflects the operating characteristics of the buyers’ refineries, Saudi Arabia expects to be able to protect its returns on its oil trade and to have more stability in prices and profitability. Whether that happens or not remains to be seen next year.

Exhibit 8. WTI/Brent Spread Demonstrates Problems With WTI

Source: EIA, PPHB

Some people believe Saudi Arabia is making the pricing switch to increase its power to influence crude oil price trends. They base that belief on the frustration the Kingdom demonstrated during the summer of 2008 run-up to $147 a barrel oil prices when it could not find buyers for the 500,000 barrels of sour crude it was prepared to sell to help to cool off the market. At that time, oil prices were being driven by a “fear” of a global supply shortfall for meeting burgeoning demand growth. Subsequent to the collapse in crude oil prices, the U.S. government began investigating the role speculators – those “thieving” capitalists – played in driving prices so high. If Saudi had been pricing its crude according to ASCI, it could have shipped additional cargos of crude to the U.S. Gulf Coast and demonstrated to the world there were sufficient crude oil supplies to meet demand, which likely would have put downward pressure on WTI prices.

It seems to us, however, that this pricing change by Saudi Arabia is reflective of a country being interested in protecting its vast wealth while not upsetting its principal customers. The weakness in the value of the U.S. dollar has not only directly impacted the worth of crude oil, but also the cost of goods and services Saudi Arabia buys. Other major trading partners of the U.S. have complained about the dollar’s value, which they see tied intrinsically to our government’s financial mismanagement of our economy. Rather than urge the creation of a new global currency standard or swapping U.S. dollars for gold as other countries have done or are doing, Saudi can retain its close relationship with Washington while protecting the value of its oil by making this oil price shift.

Exhibit 9. ASCI Tracks Middle East Prices

Source: Argus Media Ltd.

Likewise, by not taking actions that would further pressure the U.S. dollar, or possibly force government actions detrimental to global trade, Saudi Arabia helps its Asian oil consumers who are highly dependent upon the U.S. economy for their income. Additionally, this pricing move reflects the shifting mix of the supply of crude oils that are increasingly becoming heavier and sourer. Since the ASCI crude index closely tracks that of the Middle East crudes that are the pricing standards for Asia, this move by Saudi Arabia appears to be part of a consistent long-term strategy for maximizing the country’s crude oil value and reducing the potential for speculators to increase the volatility of crude oil prices. Just as the Dow Jones Industrial Index doesn’t truly reflect the value of the stock market, WTI’s role in world crude oil markets has diminished, too. We doubt either the NYMEX or CME are going to disappear with this pricing shift. Moreover, the media will continue to tell us with shorthand – DJIA and WTI – how our world is functioning every day.

Wall Street Says Energy Is Attractive Investment Sector

Barron’s recently published its semi-annual survey of money managers’ outlooks on the economy, the market and stocks. Based on the poll, which is conducted in the spring and fall by Barron’s with the assistance of Beta Research, 60% of the money managers surveyed are either bullish or very bullish on the stock market through at least the middle of 2010. This is the same bullish percentage as recorded in the spring survey even after the significant rise on the overall stock market suggesting how oversold these professional money managers viewed the market when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell to 6,547 in early March – a 12-year low.

Based on the views of the money managers, the Dow industrials could climb another 5% by year-end, putting it at 10,187. They believe the Dow could rise to 10,771 by the middle of next year. They also believe the S&P 500 stock index could rally by 8% over the next two months and then climb by another 6% in the first half of 2010. Despite this overall optimistic view of the stock market, some 80% of the respondents believe that stocks are fairly valued or overvalued now compared with 44% who held that view last spring.

Exhibit 10. Money Managers Favor Energy Stocks

Source: Barron’s Fall 2009 Big Money Poll

When asked which industry sectors would perform the best and worst over the next 6-12 months, three sectors were singled out for potentially outstanding upside: technology, energy and health care. The selection of health care probably suggests these money managers believe the stock prices have been unduly depressed by the battle over revamping America’s health care system. It also suggests that the managers believe some companies will be beneficiaries of expanded medical coverage despite the supposed cost control efforts embedded in the proposed health care legislation.

Technology always seems to be a favorite of investors because they are counting on new products and technologies that will create new, and expand existing, markets offering increased revenue and profit growth. Energy, however, seems to be a bet on the continued recovery in oil and gas prices and a resumption in demand growth due to a recovering global economy. Subsectors within energy that were singled out as particularly attractive included coal, natural gas and pipeline companies. The money managers remain neutral or bullish on oil and expect crude oil prices to trade within the $70 to $75 per barrel range. At that level there should be a resumption of oilfield activity as long as demand is not suppressed by a double-dip recession.

Based on Robert Shiller’s 10-year rolling Price to Earnings multiple, the S&P 500 stock index is slightly overvalued. As the accompanying chart shows, the current P/E ratio is 18.8x compared to the average since 1950 of 16.3x. What the nearby chart shows is how in the late 1990s when the dot.com stocks were all in the center of the investment rage the stock market was severely overvalued.

Exhibit 11. 10-Year Rolling P/E Shows Market At Premium Value

Source: Plexus Asset Management

Even after the market crash and the fallout from the 9/11 attacks the market remained consistently overvalued. The market only dropped to a discounted value with the credit crisis last fall. While stock prices have declined over the past two years, the valuations have risen as earnings are contracting. Since the P/E ratio is calculated by a rolling averaging of ten years worth of earnings, the earnings decline of recent quarters will depress the average for some extended period of time contributing to the market carrying a valuation much closer to its long-term historical average.

One of the key questions about energy stocks, however, is just how attractively valued they might be today. A study done by Ned Davis Research, based on data as of the end of September, compared the price to sales (P/S) ratio of companies in each of the ten industry sectors of the S&P 500 stock index and how they compared with their historical average seven months after reaching a bear market low. The data shows that the market has priced in loftier expectations for almost all the sectors for sales growth, or sustainably higher profit margins, or both.

All but one of the ten S&P industry sectors showed a higher ratio of current P/S valuation than existed as of seven months after the end of bear markets. Only health care stood out as significantly undervalued relative to the historical record. The research compared the current sector valuations to those experienced in the last five bear markets since 1975.

Based on the rankings, energy was the sixth most overvalued industry sector. In our view, energy’s overvalued measure reflects investor belief that oil and natural gas prices will continue to rise in the future reflecting further improvements in global economic activity. As a result, investors have been much more willing to bid

Exhibit 12. Most S&P Sectors Overvalued On Historic Pricing

Source: Ned Davis Research, Barron’s

* Dates for Seven Months After Bear Market Low are: 7/31/75, 11/30/80, 3/31/83, 5/31/91 and 4/30/02

energy company share prices up even while sales reflect the lower energy prices of past periods and earnings are certainly depressed by the fall in commodity prices and lower activity and/or sales. This data, however, does provide a counter balance to the more bullish view about energy stocks for the next 6-12 months expressed by the money managers in the Barron’s survey. Which study proves more accurate in predicting the future trend in energy stock prices will likely depend upon the course of economic activity and its impact on commodity prices. Stay tuned.

Houston Energy Employment: Is The Worst Behind Us? (Top)

The Houston Chronicle reported on a presentation by Dr. Barton Smith, director of the University of Houston’s Institute for Regional Forecasting, in which he gave his outlook on the employment situation for the Houston region for 2010. Dr. Smith proclaimed, “The worst is behind us.” His statement reflected his forecast that the region will only lose about 13,000 jobs in 2010 or 0.5% with most of the job cuts coming early in the year. By the end of the year he expects Houston to begin showing job gains. The number of lost jobs he projects for next year compares with the estimated 62,000 positions lost this year. The job decline this year equals about 2.5% of 2008’s employment total.

The article about Dr. Smith’s job market projections included a chart derived from data supplied by the Institute for Regional Forecasting showing employment trends by broad industry sectors during the past 12 months and the previous five years. The data shows that in the past 12 months only the government sector has added positions. That is not a real surprise as governments seem to grow regardless

Exhibit 13. Government Sector Only Growth In Recent Times

Source: Texas Employment Commission, PPHB

of economic conditions and especially during this downturn as public employment is being favored through government spending plans. Employment in the Mining sector, where most of the energy jobs are counted, shrank by 2.1% in the past 12 months. But this sector had shown the greatest employment growth over the prior five years – increasing by nearly 40%.

What The Houston Chronicle table doesn’t provide is a flavor for how significant each of the sectors is to the Houston economy. We went to the Texas Employment Commission (TEC) that collects and publishes labor market data to see what the September employment figures were for the Greater Houston Metropolitan Statistical Area. The Houston MSA includes Houston, Sugar Land and Baytown. It showed that in September, there were a total of 2,516,600 nonfarm jobs. Of this total, the Mining sector accounted for 90,100 positions, or 3.6% of the total. This weighting is quite interesting since Dr. Smith made the point that the dramatic fall in natural gas prices was the cause of his last year’s forecast being too optimistic. Additionally, the newspaper article quoted Bill Gilmer, vice president and senior economist for the Houston office of the Federal Reserve Bank as saying, “Houston is still a commodity-driven city…”

Those comments and the statistics drove us to examine what has happened since the great energy price bust in July 2008. To seek that answer, we compared the total Houston MSA employment picture for July 2008 with September 2009. According to the TEC data, the region has lost approximately 116,200 jobs, and of that total, 1,300 were in the Mining sector. Based on the various announcements over the past 12 months by oilfield service and energy companies headquartered in Houston, one would have expected a much greater decline in the number of positions than reflected in the Mining sector statistics.

So what’s the answer? We started going through the various employment subsectors looking for those clearly identified with the petroleum industry. In the accompanying table we have listed those employment sectors that either by their title or based on our

Exhibit 14. Mining Sector Has Barely Lost Jobs

Source: Texas Employment Commission, PPHB

knowledge of their work, we can identify as energy related. The first two categories – Oil and gas extraction and Support activities for mining – comprise the Mining sector. If we look at those two subsectors – one has gained 1,800 jobs while the other has lost 3,300. If, however, we look at the bottom three subsectors in the table identified as containing energy jobs, one is up 400 positions, one is down 800 and the last is up 100, for a total net change of a loss of 300 jobs out of a total of slightly over 60,000 positions.

Exhibit 15. Energy Jobs Changed With Overall Employment

Source: Texas Employment Commission, PPHB

The thrust of the job losses appear concentrated in the Durable goods manufacturing subsector where 15,000 positions have been lost, or almost 10% of the July 2008 employment. How good are these numbers? We know that certain oilfield sectors such as seismic equipment manufacturing have been severely impacted by the oil and gas price downturn. On the other hand, a number of oilfield equipment manufacturers entered the industry downturn with substantial backlogs that they have been fulfilling. Many of the oilfield service companies have reduced headcounts. It is likely that many of the reductions were workers involved in manufacturing equipment for the service side of their organization. What we don’t know is how they would be classified.

In contrast to the energy industry recession of the 1980s, Houston is no longer the center of oilfield manufacturing. Many of the plants from the earlier period were shut down, the jobs shipped to lower cost labor markets, either here or abroad, and the property sold for new commercial or residential developments. That shift gives us pause about accepting that all the jobs lost in the Durable goods manufacturing sector were energy ones. On the other hand, if we accept that all Durable goods manufacturing jobs are energy jobs, the 310,100 positions we have identified represented 11.8% of the Houston MSA labor market in July 2008. Surprisingly, even after the loss of 16,800 jobs, energy’s weighting in the employment picture was barely reduced to 11.7%.

The potentially more significant issue for Houston’s employment is how the energy industry’s role in the city’s employment makeup may change in the future. Several broad industry trends that could have a significant impact on energy industry employment include: peak oil, exploitation of gas shales, greater consumption of liquefied natural gas (LNG), greater international E&P opportunities and increased use of alternative energy fuels domestically. One could also add increased government and regulatory involvement in the energy industry as other forces that will impact employment trends.

For example, increased difficulty in securing work visas for foreign national employees may cause domestic energy companies to shift training and research activities out of the U.S. Exploiting gas shales would appear to reduce the required exploration skills employed in more traditional searches for hydrocarbon resources. The greater internationalization of the energy industry means more nationals as both employees and managers that may increase the pressure to locate headquarters outside of the United States. Increased use of LNG domestically may reduce natural gas exploration and drilling activity, putting a damper on employment growth, as might a clear determination about the peak oil debate. Greater adoption of alternative fuels in our energy supply mix will also change the nature of employment opportunities and where those jobs may be located. Without a greater focus on developing clean energy businesses in Houston, the city is likely to lose a portion of these jobs in the future.

Houston’s economy continues to be significantly impacted by the movement of commodity prices as they cause energy companies to expand or contract their operations. Longer term energy industry trends suggest that the impact will be diminishing over time. We just don’t know how quickly the energy industry’s impact will erode.

Contact PPHB:

1900 St. James Place, Suite 125

Houston, Texas 77056

Main Tel: (713) 621-8100

Main Fax: (713) 621-8166

www.pphb.com

Parks Paton Hoepfl & Brown is an independent investment banking firm providing financial advisory services, including merger and acquisition and capital raising assistance, exclusively to clients in the energy service industry.