- The Wildcard Of Hurricane Impact On Oil Demand

- Psychology And Dollar Index Helping Lift Oil Prices

- Have Houston Businesses Gained At Expense of Residents?

- Germany’s Diesel Scandal Is Helping Electric Vehicle Sales

- Hurricanes Harvey And Irma Spark Climate Change Claims

- Oil Prices Matter, But Then They Often Don’t Tell Us Much

Musings From the Oil Patch

September 26, 2017

Allen Brooks

Managing Director

Note: Musings from the Oil Patch reflects an eclectic collection of stories and analyses dealing with issues and developments within the energy industry that I feel have potentially significant implications for executives operating oilfield service companies. The newsletter currently anticipates a semi-monthly publishing schedule, but periodically the event and news flow may dictate a more frequent schedule. As always, I welcome your comments and observations. Allen Brooks

The Wildcard Of Hurricane Impact On Oil Demand (Top)

Parts of Florida are still without power as local utility companies, aided by repair crews from utilities across the nation, struggle to restore service to all customers. As Hurricane Irma was exiting the state, the electricity repair crews were mobilizing to begin restoring power to the 6.5 million customers who lost power due to the destruction caused by the storm. As one utility executive commented, the tract of the storm was unusual and its size was massive. As a result, rather than typical hurricane tracts that damage only one coast of the state, or cross it on a storm’s journey into the Gulf of Mexico, Hurricane Irma turned north after reaching the Florida Keys at the southern tip of the state. The storm, rather than hitting Miami and traveling up the east coast, made landfall on the state’s west coast near Naples. It then traveled north onshore, which sapped the storm’s strength, reducing the damage compared to what was projected had the storm continued along the coast and retained most of its strength. For Florida utility companies, this storm was the first time their entire service areas were impacted at one time.

Several projections were made of the impact on U.S. oil demand caused by Hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Thomas Pugh, a commodity economist at Capital Economics, said that the combined impact of Harvey and Irma would exceed that of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. That hurricane, and its aftermath, drove U.S. oil demand down by 2% versus the prior year in the three months following its landfall.

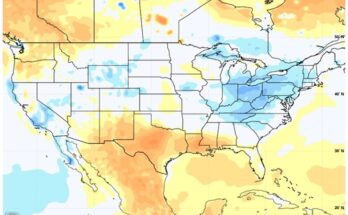

Exhibit 1. Will Katrina Oil Cut Experience Be Repeated Now?

Source: EIA, PPHB

To assess this forecast, we went back and looked at the change in oil use month over month during 2000-2009. We also calculated a 3-month moving average of the monthly changes to smooth out the monthly variability that can be caused by one-off conditions. During the time period studied, we experienced the recession caused by the 9/11 attacks as well as the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent 2009 recession. We have circled in red in Exhibit 1 the time period when Katrina hit New Orleans. During the four months preceding Katrina’s arrival, oil demand growth was positive with monthly gains as small as 0.3% to as much as 3%. Starting in September 2005, only one of the next eight months (December 2005) showed positive year-over-year demand growth. Was that all hurricane related?

Commodity economists at Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. (GS-NYSE) predicted that Hurricane Harvey would cause a “bearish shock for global oil balances.” They predicted that U.S. oil inventories would rise by 40 million barrels in the following month, raising total stockpiles to nearly 500 million barrels. In their view, this increase would negate the inventory declines experienced in July and August. From the last week in August through the first three weeks of September, domestic oil inventories have risen by 15 million barrels. As additional refineries come back on stream, the Goldman Sachs estimate may prove to be too high. Regardless, their forecast points out how sensitive global oil markets are to movements in U.S. oil inventories.

As we investigated the Harvey/Irma impact on oil demand relative to that of Katrina, we plotted the monthly levels of estimated daily supplies of petroleum products. We looked at all the years of 2000 through 2009 and then plotted the year-to-date estimates for 2017.

Due to the official monthly data delays from the Energy Information Administration, we estimated the latest two month supplies from the weekly estimates reported.

Exhibit 2. Will Harvey And Irma Outdo Katrina Oil Demand Hit?

Source: EIA, PPHB

What is evident is that demand falls in September, largely a reflection of the ending of the summer driving season and the lack of winter demand. A similar seasonal drop occurs in the spring when the nation exits winter but hasn’t entered the summer demand increase phase. While virtually every year of those studied showed the September decline, the sharpest monthly drops happened in 2005, 2008, and now in 2017. The sharper than normal drop in 2008 was related to the financial crisis that peaked at that time. The 2005 and 2017 drops appear to be tied somewhat to the impact of hurricanes, but it is impossible to attribute all the demand decline to storms. It will be important to track oil demand through the balance of 2017.

One last observation from Exhibit 2 is the level of demand. The two lowest oil demand years were 2008 and 2009. The highest demand year was 2005, until Katrina helped derail consumption. Amazingly, 2017 was showing rapid demand growth up until August, so will the hurricanes not only derail near-term demand, but also demand for longer? As domestic oil production resumes growing, the lack of an oil demand rebound presents the possibility of inventories growing more rapidly and putting downward pressure on oil prices. The lack of demand certainty is likely a reason for oil prices to be range-bound.

Psychology And Dollar Index Helping Lift Oil Prices (Top)

Crude oil prices are flirting with $50 a barrel. This is not surprising given that there is plenty of ammunition for the optimists projecting higher oil prices as they consider the state of the various factors that influence price levels. We would suggest that the following list of factors are quite favorable for higher oil prices in the near-term:

- the International Energy Agency raising its estimates for global oil demand for 2017 and 2018;

- the International Monetary Fund having recently raised its global economic growth projections;

- U.S. crude oil inventory increases have not grown in recent weeks by as much as expected given the magnitude of the shutdown of refinery capacity due to Hurricane Harvey’s flooding;

- OPEC is actively discussing extending its production cut by another three to six months, or well into 2018;

- production in several key OPEC members has declined in recent months, reducing overall supply;

- OPEC is discussing increased monitoring of its members’ oil exports rather than their production as a way to boost overall compliance;

- the U.S. drilling rig count rebound has ended as producers are now laying down rigs in response to the recent oil price weakness;

- the Energy Information Administration’s latest Drilling Productivity Report projects that U.S. oil production in October will grow by only 76,000 barrels a day, the first month since June in which output growth will fall below 100,000 barrels a day; and

- the value of the U.S. dollar has been falling, helping make oil cheaper for foreign buyers.

The last point, which is very positive for oil prices, hasn’t received as much attention as it probably should. We decided to examine the changes in the trend of the U.S. dollar index over the 1986-2017, as well as focusing on the shorter time frame of 2010-2017. The two charts help demonstrate how significant changes in the trend in the value of the U.S. dollar index, moving from stronger to weaker, or vice versa, have played in influencing crude oil prices.

Exhibit 3. Market Or Dollar, Which Influenced Oil Prices More?

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve, EIA, PPHB

As the world markets exited the first half of the 1980s, they left behind a period of extreme economic disruption due to the shock of exploding global oil prices during the 1970s, the loss of substantial oil output following the Iranian revolution in 1978, the requirement for dramatically high interest rates in order to break the extremely high inflation rates of the second half of the 1970s, and a severe and prolonged global recession. That recession curtailed oil demand growth, upsetting the controlling power in the oil market – OPEC – and forced the world to deal with a flood of petrodollars, created by the 1970s’ high oil prices, which fueled dramatic domestic consumption and building booms in most Middle East oil producing countries.

The collapse of oil prices in 1986 marked the temporary ending of OPEC’s power, which also coincided with the ending of the recession and the resumption of global growth, much of which was driven by investment by countries that needed to reduce their economies’ energy intensity. The Middle East building boom reflected another example of a global economic imbalance that impacted the world’s energy markets.

As the U.S. economy rebounded and led the global economic recovery, the U.S. dollar grew stronger, but the oil market’s demand and supply dynamics actually helped to hold down oil prices until 1998. At that time, Asia was experiencing rapid growth, which sparked OPEC to boost its output. That decision came just as the Asian currency crisis exploded, undercutting economic growth at the same time oil supply growth was rising. The crisis drove the U.S. dollar index higher, while at the same time depressing crude oil prices. This situation continued until early in the 2000s when the dollar index peaked and crude oil prices began rising. They rose to record highs just as the 2008 Financial Crisis exploded on the scene. That crisis and its resulting recession created extensive volatility in the dollar index and crude oil prices, but the impression from the chart is that both indices moved largely sideways until into 2014. At that point, the dollar index began rising once again, and crude oil prices collapsed. Again, oil market supply and demand conditions were favorable for the price collapse. As oil prices bottomed, the dollar index ceased rising and the two indices again exhibited limited movement until recently.

Exhibit 4. Dollar Weakness Should Have Raised Oil Prices

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve, EIA, PPHB

Turning to the chart of more recent oil prices and the dollar index, the inverse relationship between them shows how important a stronger dollar was in maximizing downward pressure on crude oil prices. Although the dollar’s value since late 2016 has weakened, it has not materially helped oil prices by as much as would have been expected because oil industry supply/demand dynamics were not accommodative for higher oil prices. If the dollar index continues declining (a questionable assumption), the improved oil market fundamentals – higher demand and less supply – should support oil prices working higher over the next few months; how high is difficult to project. Will the dollar index continue to decline in light of the Federal Reserve Bank’s decision to start unwinding its $4 trillion balance sheet? Will the dollar’s value matter if oil supplies are further restrained and demand remains healthy? These are the big questions left unanswered. They will have much to do with the future direction in oil prices but we can only speculate. And, in our view, it is better to monitor the trends than speculate.

Have Houston Businesses Gained At Expense of Residents? (Top)

As the floodwaters from Hurricane Harvey were still swirling around, forcing thousands of Houstonians to flee their underwater homes and cars, critics of the city and its homebased energy industry were crying out about how business had ripped off the residents. Underlying the claims was the belief that the lack of zoning in the nation’s fourth largest city was the root cause of the flooding. According to the critics, the primary beneficiary of the lack of zoning, and the tax breaks from the city was the business community, especially the energy companies. We dealt with the zoning issue in our last Musings, but left alone responding to the other claims about Houston’s business community.

In reading many of the media articles about the supposed failings of Houston, we were left with an understanding of how many of the authors knew little of Houston’s history and how it works. Moreover, they showed that they never investigated how the city became the most dynamic city in the nation during 2010-2016, with population growth of 500,000 people, a 12.5% increase. We suspect most of the critics aren’t old enough to appreciate how Houston went from a weak peer to its neighbor to the north, Dallas, during the 1960s and 1970s, only to pull ahead of it over the past 35 years.

At the heart of the Houston criticisms was the city’s embrace of the petroleum industry, which held responsible for the human-induced carbon emissions destined to end our society in the distant future unless they are curtailed. While the critics realized that Houston wasn’t about to exile the energy business, they decided to see if by characterizing the industry as ‘rip-off’ agents they might be more successful in painting it as the agent of blame. The critics are hoping that the city’s residents might be swayed to turn on the city’s energy community. What the critics fail to understand is how intertwined the city of Houston is with its business community. Moreover, they failed to appreciate how responsible that symbiotic relationship has been for the enhanced lifestyles of its residents, which is developed due to a robust job market created by the rapid growth of Houston’s corporate community, especially its energy business. The critics demonstrated that they did not learn of the many contributions of Houston’s energy and business leaders over the years that fostered the city’s growth.

Exhibit 5. Houston Founded As A Real Estate Play

Source: Houston Planning Department

A key ingredient for Texas municipality growth is the ability, under the Texas Local Government Code, to change a town’s boundaries either by annexation or disannexation of contiguous property. While the mechanics were changed in the late 1990s as a result of Houston’s annexation of the noncontiguous Kingwood neighborhood, the city has used annexation to grow from 147 swampy acres at the confluence of Buffalo and White Oak Bayous in 1836, when the Allen brothers founded the city, to 667 square miles over 181 years. This annexation history is important to understanding the role business leaders played in the growth of Houston.

Exhibit 6. Houston’s Size 181 Years After Founding

Source: Houston Planning Department

Annexation allows the city, via a strictly prescribed process and with the approval of the residents in the area to be annexed, to absorb contiguous acreage. The city is obligated to provide all city services to the new residents, while it is able to level its taxes on the real estate in the acquired area. Why was this critical for the relationship between business and the city? In the past, when companies headquartered in downtown Houston considered moving their headquarters, or establishing major office/research facilities outside of the city’s boundary, they knew that ultimately they would be annexed back into the city. Therefore, business leaders – especially those with the rapidly growing oil companies – knew that to protect their companies and their employees, they needed to become more active in dealing with the city’s growth issues. In other words, one could not escape the clutches of the city, and its problems, merely by relocating from the center of Houston. You were guaranteed to be recaptured. That realization was a key reason behind business leaders becoming, and remaining, active, in conjunction with civic leaders, in dealing with the major social and economic issues confronting the city.

This business/civic involvement dates from the founding of Houston, which was actually a speculative real estate venture in 1836. It was fitting that the city moved on from real estate speculation to global oil exploration and medical technology breakthroughs. One could also throw in space exploration, given NASA, as another driver for the city’s growth. As a result, the role business visionaries have played in the growth of Houston cannot be understated.

How many people are familiar with the 8F Crowd? No, we are not talking about a shoe size. 8F was the suite number at the Lamar Hotel located at 921 Lamar Street in downtown Houston. The 16-story hotel was built in 1927 by Jesse Jones, a successful businessman and Democratic politician. The hotel was constructed on the site of a lumberyard operated by Mr. Jones, and he made his home for three decades in the suite on the 16th floor. According to the last manager of the hotel, 88 of the 350 rooms were permanently leased by major figures involved in oil, politics, banking, cotton, newspapers and the law, along with other industries. The hotel and an adjacent building were imploded in 1985 and the site is now home to 1000 Main Street.

The 8F Crowd was a small collection of the movers and shakers in Houston, Texas and nationally, especially in Democratic politics, from the 1930s through the 1960s. They comprised the visionaries that helped make Houston what it is today. The suite was dubbed the "unofficial capital of Texas" as the 8F members plotted the growth of the city and state, while providing many of the political leaders that made it happen. Many of these leaders also played important roles in the federal government during the Great Depression and World War II.

Exhibit 7. Postcard Advertising Lamar Hotel

Source: Boston Public Library

Suite 8F was leased by George Brown and paid for by the Brown and Root Construction Company, formerly a part of Halliburton Company (HAL-NYSE) and now the core of KBR (KBR-NYSE). Mr. Brown was largely responsible for the emergence and rise in power of Lyndon B. Johnson. Besides Messrs. Brown and Jones, other giants of the Houston business community who were part of the 8F Crowd included: Gus Wortham, founder of American General Insurance Company, now part of AIG (AIG-NYSE); Walter Mischer, a real estate developer, banker (Allied Bank, now part of Wells Fargo (WSF-NYSE)) and construction executive (Marathon Manufacturing), who convinced the Texas legislature to allow the establishment of municipal utility districts that facilitated the growth of Houston and other cities in the state; James Abercrombie of Cameron Iron Works, now part of Schlumberger Ltd. (SLB-NYSE);

William Vinson, a co-founder of the powerful Vinson & Elkins law firm; and “Judge” James A. Elkins, builder of First City National Bank and Texas Eastern, the giant pipeline company; and Herbert Hunt of the famous Hunt oil and silver family.

On the political front, there was Sam Rayburn, the longest serving Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives; John Connally, Governor of Texas who was wounded in the President John F. Kennedy assassination; William P. Hobby, Governor of Texas; and Lyndon B. Johnson, President of the United States. All of these powerful leaders owed their success to the political and financial support of the 8F Crowd. There are many stories of Pres. Johnson spending his early political years mixing drinks for the poker-playing 8F Crowd members. There is not enough time to detail the history of the 8F Crowd, but understand, the members were powerful and generous. (We were fortunate to have met and dealt with a number of these leaders.)

Besides overseeing the growth of the Texas Medical Center and helping promote both the growth of Rice University and the creation and growth of the University of Houston, these men led the charities that helped establish and grow the libraries, museums, health centers, schools, and local welfare programs that helped shape Houston. One of the most visionary moves engineered by these leaders came in the late 1950s, when they, along with city officials, realized that the city’s municipal airport (now Hobby Airport) would be inadequate to meet the projected growth of the city and region. They envisioned the jet plane era and the importance an international airport would play in connecting Houston to the world.

In 1957, these leaders formed a partnership, Jet Era Ranch Corporation, to push for a new airport and to ensure that the vision came to fruition. The partnership began purchasing title and deed rights to roughly 40,000 acres located 23 miles north of downtown Houston. A clerk’s typographical error transformed Jet Era into Jetero, which became the name for the official planning documents for the airport until 1961. Jetero Boulevard was the name of the road providing the eastern entrance to the airport until it was renamed Will Clayton Parkway.

Houston annexed the Intercontinental Airport area in 1965, and it began operations in 1969, at which time all commercial airline operations were moved from Hobby Airport. That airport was limited to private aviation, until Southwest Airlines (SWA-NYSE) began operations in the early 1970s. The point of this discussion is to show how the 8F Crowd foresaw the need for a new, bigger airport to meet the needs for the international reach envisioned by civic and business leaders. They provided the financial resources to acquire the property without driving up the cost, as would have occurred had the public been alerted to the city’s plans, which would have happened had everything been left to the local government.

While the critics decry the involvement of the business community in helping formulate and achieve the growth Houston has experienced, the symbiotic relationship has worked well for decades. If the critics had their way, Houston would look more like New York or Chicago with the office buildings of Greenway Plaza, the Galleria, the Energy Corridor and Greenspoint all being located in downtown Houston. Would we be better off? Instead of remote offices buildings, shopping centers and parking lots and garages, we would swap them for remote parking lots to service the workers who are envisioned to have been using surface mass transit. Would everyone live and work downtown? For decades, downtown Houston had the reputation of “rolling up the sidewalks” after 5 pm. Today’s vibrant Houston downtown is a function of developers who began speculating in the 1990s that they could offer a lifestyle many people – young and old alike – would desire. The city’s evolution is changing, and it will change in the future in response to the learnings from Harvey and the growth of our multi-cultural and younger population. That doesn’t negate the successful relationship between big business and Houston’s city leaders that created the dynamic city we have today. In fact, the city has turned to retired Shell Oil CEO Marvin Odum as Houston’s new chief recovery officer. This is another example of the city benefitting by tapping the management skills of big business. It is an excellent example of business and government working together. A study of Houston’s history, and especially the contributions of big business, including the energy companies, would have served the city’s critics better.

Germany’s Diesel Scandal Is Helping Electric Vehicle Sales (Top)

The German election campaign eventually extended beyond the Chancellor Angela Merkle’s policy on the treatment of refugees to include her somewhat indifference towards the country’s auto industry’s scandal in cheating on diesel emissions tests. Germany’s auto industry pioneered the diesel engine, which enabled its companies to prosper, by delivering high performance vehicles to buyers, especially those at home. The discovery of the manipulation of engine control software, which enabled emission test cars to cheat and meet regulatory standards while production vehicles were not in compliance, led to the payment of billions of dollars in fines and the overhaul of managements and boards of directors of the violating companies. Questions have been raised about the viability of the German auto industry in the rapidly changing global industry.

The auto industry in Germany, as well as most of Europe, is finding its growth limited due to demographic trends and the push by local governments to outlaw cars with internal combustion engines (ICE). Even the lucrative U.S. auto market is becoming increasingly competitive as it experiences slowing growth after rebounding from the 2008-2009 recession. That growth will slow more if the federal and/or state governments adopt the electric vehicle (EV) solution to combat climate change fears. As a result, German car manufacturers seeking to grow are now targeting aggressively developing economies, with China presenting an attractive target. The sudden embrace of EVs by China, in response to its government’s energized effort to fight climate change, created a dilemma for Germany’s auto companies – either adapt or die.

The latest car sales figures show how Germany’s auto market is changing in response to the diesel scandal. The figures also show how German auto companies are adapting to the new market dynamics of EVs. For the month of August, diesel sales in Germany fell 13.8%, while gasoline vehicles rose 15%. Clean vehicle newsletters are trumpeting the EV growth in Germany, as well as throughout Europe, but the numbers remain small.

Battery electric vehicle (BEV) registrations increased by 137% in August. At the same time, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) sold soared by 214%. Combined, these two vehicle classes reached 1.88% of German’s total auto sales for the month, according to Clean Technica. While this penetration rate is nearly twice that of EVs in the U.S., the 4,795 EVs sold in Germany in August pale in comparison to the 11,000 to 18,500 monthly EV sales in the U.S. this year. The most significant development in the latest German car sales data is that of the 30 EVs listed on the sales chart supplied by Clean Technica, 19 of the EVs come from Mercedes-Benz, Audi, Smart, Volkswagen or BMW.

Exhibit 8. Is Hybrid Acceptance The Message For EVs?

Source: EAFO, PPHB

Looking at overall European EV sales data shows another interesting trend. Exhibit 8 shows EV sales, divided by BEV and PHEV models, for the 32 countries that make up newsletter’s definition of Europe. Their definition includes the 28 countries of the European Union plus Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Turkey. The chart shows how explosive EV sales have been in Europe, as the market only emerged in 2011. The year-to-date data for January through July showed total EV sales of 148,051 units, up 36%. If 2017 EV monthly sales are annualized, the year will post a 133% increase over 2016’s sales.

What we noticed in examining the sales data is how PHEVs have accounted for over half the total EV sales in Europe starting in 2015. That is an important point as many European countries and cities are moving to ban the sale of ICE vehicles with deadlines ranging from 2025 to 2040. Much has been made of the announcement by the Swedish car company Volvo that it will only build electric or hybrid cars beginning in 2019. While all the vehicle models will need to be plugged in for recharging, hybrids provide a solution to range anxiety. As Europe appears to be demonstrating, hybrid vehicles may be the majority of EVs sold, offering some respite for the widely dismissed petroleum industry. Gasoline may have a longer future than the EV optimists anticipate.

Hurricanes Harvey And Irma Spark Climate Change Claims (Top)

After 12 years of escaping landfall of a major hurricane, the United States was slammed by two massive storms – Harvey and Irma – landing within weeks of each other, almost right on top of the seasonal peak (September 10th, for tropical storm activity in the Atlantic Basin). This being a non-El Niño year means less wind shear is present to rip apart hurricanes and inhibit their formation and strengthening. The lack of wind shear has contributed to the very strong storms experienced this season, as sea surface temperatures are especially warm, which is the primary driver of stronger storms.

The first of the storms, Hurricane Harvey, which flattened Rockport, Texas, became trapped between two massive high pressure centers over parts of the U.S. and was unable to exit from the Texas Gulf Coast region for days. As result, massive amounts of rain fell – the equivalent of a full-year’s rainfall in barely three days. The geography of the Gulf Coast made it impossible for so much rainwater to drain away quickly; thus severe flooding was experienced in many areas.

It was estimated by meteorologist Ryan Maue of WeatherBell that 27 trillion gallons of water fell over Texas and Louisiana. The weight of the water, at eight pounds per gallon, has compressed the earth’s surface in the Houston region. A Jet Propulsion Laboratory researcher, Chris Milliner, posted a plot of the change in GPS station elevations in the Houston region immediately following Hurricane Harvey. (Exhibit 9, next page.) The data showed Houston’s elevation being lowered by two centimeters, a minor amount, but significant because it is rare for any weather event to have such an immediate and measurable impact. The expectation is that once the region dries out, Houston’s elevation will rebound.

Exhibit 9. How Houston’s Elevation Was Lowered By Flood

Source: Jet Propulsion Laboratory

The flooding of Houston and the devastation of southern Florida by Hurricane Irma two weeks later has re-energized the 2005 claims that these severe storms are being spawned and intensified by climate change due to carbon emissions from fossil fuels. Therefore, to stop hurricanes, we should eliminate fossil fuels and repower the world’s economy with renewable fuels – solar, wind, hydro, and possibly nuclear power. A sub-debate is whether there is, or needs to be, a role for nuclear power in our future electricity generation system.

While trying to avoid wading into the climate change swamp and severe weather events debate, we were drawn to recent data about the status of carbon emissions, both in the U.S. and globally. It was fascinating to read the report of the “Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2015” published by the Environmental Protection Agency in April 2017. Equally interesting was researching the reports of the scientists from the University of East Anglia and the Global Carbon Project, along with those of the World Meteorological Organization. The latter two reports were issued in mid-November 2016, but we don’t recall there being much attention paid to them.

The bottom-line of the Global Carbon Project report was that the amount of CO2 sent into the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels, gas flaring and cement production has held steady for three years in a row. The data shows that global fossil fuel emissions grew by 0.7% in 2014, but then experienced no change in 2015, and based on preliminary data for 2016 was likely to show a rise of barely 0.2%. This is a remarkable change in pattern given that the average annual rate of carbon emission increases experienced during the 2000s was 3.5%. Measured over the decade of 2006-2015, the rate of emissions increase was only an annual average of 1.8% per year. The recent decadal performance was helped by the dramatic slowing of emissions in these most recent years. A series of charts from the Global Carbon Project demonstrate both the recent global emissions progress, as well as highlight issues remaining for further cleaning of the world’s atmosphere.

Exhibit 10. Are Global CO2 Emissions Peaking?

Source: Global Carbon Project

Other than the extended 1980s recession, due to the global energy market readjustment in response to the explosion in crude oil prices during 1973-1978, there have been only a few brief periods when carbon emissions increases flattened or declined slightly. The emissions record makes the recent trend of 2014-2016 that much more significant. As expected, environmentalists such as Dr. Glen Peters, a senior researcher at the Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research in Oslo and project manager of the Global Carbon Project, are unwilling to reach that conclusion. “Emissions have levelled out, but it’s too early to say whether that’s a peak in global emissions. First of all, we’d need to see emissions going down…Then after that, we’d need several years, maybe even a decade, to be confident that it was actually a peak,” said Dr. Peters.

Based on this test, if 2016 witnessed an actual decline in carbon emissions, which was a potential outcome acknowledged by the forecasters, it will not be until 2026 or later before Dr. Peters would accept that carbon emissions had peaked.

Exhibit 11. US Has Cut CO2 Emissions Substantially

Source: Global Carbon Project

Another chart from the report shows how per capita emissions are trending globally, and for four major polluters – the United States, Europe, China and India. While the U.S. has the highest per capita emissions, they have been trending lower for a longer period than those of Europe. Both China’s and India’s per capita emissions are rising, which is helping to keep the rise in global emissions flat. This chart is the ammunition for anti-fossil fuel campaigners who claim that, besides switching the world to clean power, we also need to restrict population growth. China’s low per capita emissions is a reflection of its large population, as the country is now the world’s largest polluter.

When total emissions are tracked by country (Exhibit 12, next page), the significance of China’s role in the world becomes clear. China’s recent emissions improvement is in direct response to the country’s switch away from coal for generating electricity. Total U.S. carbon emissions is in an established, albeit variable, downtrend, as is Europe’s, but notice how after surpassing Europe at the beginning of the 1980s and then peaking about 2005, the gap has been closing. India’s emissions continue to rise, which is largely due to the country’s high reliance on coal to generate electricity, and without a policy change, will likely become a more significant issue for the world.

Exhibit 12. CO2 Emissions By Major Countries

Source: Global Carbon Project

When tracked by source, the impact of reduced coal use in the U.S., China and parts of Europe becomes clear as the primary reason for the slowing of total carbon emissions. Switching from coal to natural gas has contributed to the improvement, helped also by increased use of renewable fuels.

Exhibit 13. CO2 Emissions By Fuel Source

Source: Global Carbon Project

Turning to the United States and its carbon emissions performance, a major contributor has been the shift in fuels used to generate electricity, along with efficiency gains in the power sector. Coal use in generating U.S. electricity peaked in 2007, and has steadily fallen, largely replaced by increased natural gas use. Renewable fuel consumption has also grown over that time frame. Exhibit 14 on the next page shows the history of electricity generation by fuel source since 1990.

Exhibit 14. How U.S. Electricity By Fuel Has Changed

Source: EIA

To better understand the impact of fuel shifts on carbon emissions, we examined the changes in the composition of the U.S. electricity market between 2005 and 2015. Between those years, power generation was essentially flat (+0.5%), while at the same time, carbon emissions fell by 21%. As can be seen from Exhibits 15 and 16, coal’s share of the power generation market declined from 50% to 33%. At the same time, the share of electricity generated by natural gas rose to 33% from 19%. In 2015, coal and natural gas had similar generation shares. Simultaneously, the use of renewable fuels increased from 2% to 7%, while nuclear and hydro market shares were essentially unchanged.

Exhibit 15. Coal Dominated Power Market With High CO2

Source: EIA, PPHB

Exhibit 16. Natural Gas Share Gain Helps Reduce CO2

Source: EIA, PPHB

The impact of this fuel mix shift on carbon emissions was significant. When we calculate the carbon emissions per million British thermal units (Btus) for each fossil fuel, we find that between 2005 and 2015, coal’s emissions fell by 34%, versus the overall emissions decline of only 21%. The offsetting factor was that natural gas emissions rose by 75%, reflecting its increased role in generating power. The decline in total petroleum emissions was virtually negligible, although percentage-wise it was 66%.

The trend in the power market’s carbon emissions is down as the fuel mix is steadily shifting toward cleaner fuels than coal. From the perspective of overall carbon emissions for the U.S. economy, our transportation sector is also becoming cleaner as the vehicle fleet has a greater share of newer, cleaner vehicles, both cars and trucks. The increased penetration of electric cars in America’s vehicle fleet will, over an extended time frame, further reduce total emissions. While the handwringing about global carbon emissions may be acceptable, the progress made by the United States, and its continuing gains, should be acknowledged. Yes, we need to continue to reduce carbon emissions, but we will achieve those gains with a cleaner power industry fuel mix and more efficient vehicles; trends that are well established.

Oil Prices Matter, But Then They Often Don’t Tell Us Much (Top)

Do you ever marvel at the national news shows always commenting on what the stock market did that day? While most Americans have an interest in the performance of the equity markets because their retirement savings are invested in stocks, but virtually no one is invested in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. If anything, it is likely they have an investment that mirrors the performance of the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index.

The reason news anchors speak of the market’s performance is that it is an instant measure of happiness. If the market is higher, the viewers are happy, and likewise, if the market is down, they feel poorer and less happy. In a few seconds, a viewer has received a message. One can liken the comments about the state of the market to a picture, which reportedly is worth a 1,000 words!

Do oil prices play a similar role in the industry as the stock market indices play for the general public? In contrast to a stock market index, the price of a barrel of oil carries a true economic benefit – it is what the oil producer is being paid for his oil. The problem is that not all oil is the same. Therefore, oil receives a price tied to its quality. Many people are familiar with the bitumen oil from Canada’s oil sands region and the heavy oil from Venezuela’s Orinoco tar sands. Because those oils have an API gravity rating below 20o, they are difficult to transport and refine, especially into the light petroleum products desired by today’s economies. As a result, these unusually heavy oils are heavily discounted from the traditional measures of oil prices – the United States’ West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Europe’s Brent.

Every barrel of oil receives a price based on its characteristics – degrees of lightness (how easy it is to refine) and quality (amount of sulfur, another refining challenge). Crude oil characteristics are only one aspect of prices that determines what actually reaches the coffers of a producer. Oil that is remotely located usually necessitates greater transportation efforts, often resulting in price cuts to reflect the additional cost.

Another market factor impacting oil revenues is whether the production has been pledged to someone in response to them offering to pay a different (higher) price than currently available if the oil can be held for delivery in some future time period. This hedging of production at higher prices takes advantage of oil speculators capitalizing on shifting market sentiment or events that might drive current oil prices higher. When that happens, the speculator will sell his contract to this future supply. Hedging oil production has enabled producers to operate at higher activity levels than implied by the amount of revenue generated with oil at current levels.

So far this year, crude oil prices have mostly traded within a range of $45 to $50 a barrel. Breaking the $50 a barrel threshold is anticipated to help drive drilling activity higher, as producers become more comfortable that higher oil prices are here to stay. Then again, producers may just pocket the extra income. In other words, the reports of daily oil price movements play the same role as the reports of the stock market, and they provide similar happiness messages. The big question is whether we can use oil price movements as the indicator of future oilfield activity?

The traditional way oilfield activity is measured is through the weekly drilling rig count reports from Baker Hughes. The reason this report is closely watched is its long history of measuring activity, having existed since 1944. What we have learned from observing the rig count over decades is its tendency to follow oil prices. That is not surprising as producer cash flows come from future output and oil prices. The prospect of higher future oil prices, and optimism about more output, is what will drive more drilling.

Exhibit 17. Drilling Activity Follows Oil Prices

Source: EIA, BEA, Baker Hughes, PPHB

Exhibit 17 shows how nominal and inflation adjusted oil prices from 1968 to now have led movements in the drilling rig count. What is also noteworthy is the rig count peak in 1981, when crude oil prices peaked and began falling. That record surge in drilling was stimulated by the perception that the industry’s future had been altered in the 1970s and the high rate of growth was necessary to supply the oil needed in the future. That future evolved from U.S. oil output peaking in 1970 and increasing the country’s dependence on greater oil imports. OPEC’s Oil Embargo price hike in 1973 and the Iranian Revolution supply-cut jump in 1978 reinforced the need for more drilling. What the world discovered, however, was how dramatic price hikes force people to alter their oil use habits.

The 1981 oil price peak was followed by a decade of lower oil consumption, which reduced the need to drill more wells. The outcome decimated the oilfield industry that had been constructed on a foundation of debt. (Does that sound familiar today?) What is interesting is observing the path of crude oil prices and the drilling rig count during the first half of the 1980s. Exhibit 18 shows the paths.

In the early years, there was a difference between domestic and imported oil prices, with the latter price higher. Oil prices slid from a peak at the start of 1981 to a near-term bottom in early 1982, before climbing briefly and then remaining level through the end of the year. Oil prices once again resumed declining, and the rig count fell more.

As shown, the first drop in the rig count eliminated 2,119 rigs. After a brief uptick in rig activity, the industry experienced a second drop, costing it 550 active rigs. From early 1983 through the end of 1984, oil prices proved stable, yet the rig count rallied, dropped, and then rallied again, raising questions about what oil prices were signaling.

Exhibit 18. 1980s Oil Price Belief Established Rig Activity

Source: EIA, Baker Hughes, PPHB

During that time, Saudi Arabia was vocal about defending the OPEC target oil price despite the cheating by its fellow members. As oil demand’s weakness became more meaningful, the effort to defend the OPEC price target became too great, forcing OPEC to accept lower target prices. That acceptance resulted in the rig count declining again. The decline ended and the rig count then remained level as hopes were high that Saudi Arabia would be successful in defending OPEC’s target price. Then Saudi Arabia’s oil minister Ahmed Zaki Yamani announced that his country had yielded too much market share and would no longer defend OPEC’s oil price. In fact, it began pumping more oil. As shown in the chart, the drop in the oil price, as well as the rig count fall, were nearly simultaneous. Both measures bottomed at the same time, but the damage done to the global oil industry and the oilfield service business required years to repair.

The lesson from the 1980s oil price and rig count history is that once oil prices reflect the reality of what the oil market of the future will look like, rig activity stabilizes. In other words, the oil price defines the “normal” that will drive future activity. We looked at the history of the 1980s – both oil prices and rig count – and that of the 2014-2017 period. When one examines recent history, it becomes clear that even following the sharp oil price drop and the subsequent sideways movement and then rebound, the rig count didn’t really reflect any improvement. The oil price action suggested that there was further downside to come, which actually happened. As a result, the rig count also fell, with both it and oil prices bottoming about 20 months after oil prices had peaked in June 2014. With the subsequent oil price rally, drilling activity also rose, but when oil prices became narrowly range-bound, the rig count climb stopped rising and began reflecting a tighter range, also.

Exhibit 19. Oil Price Normal Sets Rig Activity

Source: EIA, Baker Hughes, PPHB

The conclusion we come to is that oil prices establish a mindset among the producing sector, which sets the drilling activity. The mindset of the oil industry is settling in to the idea that prices will remain around $50 a barrel. This suggests a slight rise in the drilling rig count is possible, but a flat trend line for the foreseeable future is also possible, at least until oil prices establish their new “normal.” We believe the “lower for longer” mantra has been embraced by the industry, and it will guide activity for a long time to come.

Contact PPHB:

1900 St. James Place, Suite 125

Houston, Texas 77056

Main Tel: (713) 621-8100

Main Fax: (713) 621-8166

www.pphb.com

Parks Paton Hoepfl & Brown is an independent investment banking firm providing financial advisory services, including merger and acquisition and capital raising assistance, exclusively to clients in the energy service industry.