- Natural Gas Struggles To Stay Afloat; Time For A Change?

- Climate Movement: Why Rebranding Is An Important Move

- Alice, The Electric Plane, Was A Hit At Paris Air Show

- Can America’s Team Score Big In The Natural Gas Market?

Musings From the Oil Patch

July 2, 2019

Allen Brooks

Managing Director

Note: Musings from the Oil Patch reflects an eclectic collection of stories and analyses dealing with issues and developments within the energy industry that I feel have potentially significant implications for executives operating oilfield service companies. The newsletter currently anticipates a semi-monthly publishing schedule, but periodically the event and news flow may dictate a more frequent schedule. As always, I welcome your comments and observations. Allen Brooks

Natural Gas Struggles To Stay Afloat; Time For A Change? (Top)

If there is one sentiment that is universal in commodity markets, it is that natural gas is dead. “Stick a fork in it!” The near-month natural gas futures price was $2.34 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf) last Friday. The price has averaged less than $2.34 over the past 20 trading days, the lowest price since 2016. Compared to a year-ago, current prices are 60-cents/Mcf lower. The simple explanation for the extremely weak gas market is: too much production and not enough demand due to cool weather.

Exhibit 1. Gas Prices Scraping The Bottom

Source: EIA, PPHB

The shale revolution has driven production substantially higher than anyone ever thought possible, completely upending prospects for how the U.S. gas industry’s future was going to unfold barely a decade ago. Rather than striving to keep production from continuing to fall and forcing us to meet growing demand via pipeline and LNG imports, we are now into a surplus condition as hydraulic fracturing has opened up significant gas resources previously thought to be untouchable. Low gas prices have driven coal demand out of the power generation market, opening up the market for gas, while also shifting the U.S. into a gas exporter rather than an importer.

Growing gas production has also allowed buyers to worry less about having substantial volumes in storage to meet winter demand. Therefore, buyers see little need to lift gas prices to encourage storage injections. That dynamic has been demonstrated by the low level of storage we reached last year, and now how quickly we are rebuilding storage, while also meeting increased gas consumption from the power and export markets.

Exhibit 2. Gas Storage Rapidly Rebuilding

Source: EIA, PPHB

Exhibit 3. 2019 Weekly Injections Higher Than 2018

Source: EIA, PPHB

The recent gas production growth, which accelerated starting in 2016, appears to be slowing. To some degree, it is a function of the Permian Basin crude oil pipeline capacity shortage, which has restricted associated natural gas output. Will that change when the new oil pipelines begin operating later this year? Only time will tell, but official forecasts call for a slowdown in the growth of gas production. That means the bigger question for the natural gas market will be demand.

Exhibit 4. Shale’s Success Upended Market View

Source: EIA, PPHB

A recent webinar on the natural gas market and outlook through 2020 had two charts we found very interesting. The first dealt with the significantly different gas storage picture in Europe. Today, storage is well ahead of last year, which may have an impact on the amount of future liquefied natural gas (LNG) shipments. So far, it appears to have had little impact, but the lack of clarity about output levels from the Dutch gas fields could also impact the market for U.S. LNG shipments to Europe.

Exhibit 5. Higher Europe Gas Storage Hurts Demand

Source: EBW

The most interesting chart was explaining the firm’s gas price forecast compared to the NYMEX futures strip price. The forecasters were able to frame their perspective about the upside and downside to their forecast by listing and quantifying the positive and negative factors for gas demand and supply. We are not endorsing the forecast, but rather pointing out that there are a number of plusses and minuses that need to be considered when making a gas price forecast.

Exhibit 6. How Gas Price Forecast Could Change

Source: EBW

The natural gas market seems befuddled. To borrow an expression: “It can’t seem to get out of its own way.” Barring some dramatic event in the near-term, gas prices are likely to remain under pressure. The late start to summer in the Midwest and Northeast has undercut demand, at the same time there has been a slight slowdown in LNG shipments. If this hurricane season impacts the Gulf Coast LNG terminals and/or LNG shipments, that consumption outlet could back up into storage further depressing demand. While not an encouraging outlook, commodity markets are known for reversing just when the consensus believes prices will never change. For some reason, this feels like a possibility.

Climate Movement: Why Rebranding Is An Important Move (Top)

Energy makes the world go around, and it also seems to be what makes people crazy. Without energy, the world would not be as developed as it is, or our standard of living as high. Starting with fire, our energy sources transitioned to those more efficient and with higher energy content, as well as easier to use fuels. Today, the world’s energy supply continues to be dominated by fossil fuels – coal, oil and natural gas. These fuels account for 81% of the world’s total energy used in 2017, according to Enerdata. Forecasts suggest fossil fuels will remain dominant for decades to come. Because each fuel releases carbon into the atmosphere when burned, collectively, they have moved from being the primary drivers of improving economic futures and higher living standards, to targets of social pain for their degrading of the planet’s climate.

While fossil fuels have been held in exalted status for their ability to power the global economy to its present heights, provide a standard of living that exceeds all past history, and lift millions of people out of poverty, they were never without problems or critics Whether it was child labor in mines, black lung disease, smog and pollution, oil spills and well blowouts, or commercial dominance and unfair business practices, to name a few, the fossil fuel industry has sacrificed others in its pursuit of profits. These abuses have mobilized the energy industry’s critics in the past, but never more than now.

Fossil fuels are not moral in their own right, but what they have enabled mankind to accomplish, i.e., raise living standards, is moral. Today, many people believe the evils of fossil fuel are destroying our planet and therefore immoral. While their critics would not agree, this morality characterization of the debate over the future of fossil fuels is what has turned this into a religious discussion. If you don’t believe in climate change, you are evil and immoral.

The goalposts separating the moral extremes are about as far apart as ever. The spread highlights the ideological battle being waged over the climate and energy. In religious wars, morality, or lack thereof, is what generates the debate, but to facilitate it, labels becomes critical. Labels can be used for defining issues and measuring their seriousness. The evolution of “global warming” into “climate change” and now “climate emergency” is a reflection of this need. This evolution may also reflect a problem the climate religion is facing with its mission.

The planet’s climate has been constantly changing since our universe was created. As a result, we have millions of years of climate data, either absolute or in proxies, allowing us to trace the planet’s environmental history – its atmospheric composition, its temperature, and its livability. Proxies include ice cores, tree growth rings, sedimentary buildup in oceans, and geological strata buried in land masses. The challenge is uncovering and interpreting the data, and learning from it.

When man became educated, his curiosity led to the development of science and history. Scientists began investigating nature’s workings. These experiments were captured in history. In more recent times, modern technology allowed us to gather more and better climate data via weather balloons, measurement stations, satellites and ocean buoys. These technologies enabled the capture of better and more frequent data. But the world’s population growth has compromised the data in some cases. More people has led to higher population density, often encroaching on weather stations, as well as boosting temperatures – something known as “heat islands.” Scientists work hard to ensure the comparability of time-series weather data, but this often requires adjusting the raw data measurements opening up analyses to potential mischief.

Before going further, it is important that to note we are not judging climate science. Instead, we want to explore the topic of climate science and its politicization. Climate, and the politics surrounding it, will reshape today’s energy world and increase the challenges energy company managements face in navigating the future.

One of these challenges is the politicization of climate science. In the “2018 World Energy Outlook,” published by the International Energy Agency, Dr. Fatih Birol, the executive director, stated, "Over 70% of global energy investments will be government-driven and as such the message is clear – the world’s energy destiny lies with decisions and policies made by governments." This reality has inflated the significance of the climate science debate, as it will influence the public and, in turn, drive politicians to act and reshape the world’s energy structure.

Climate science is an extremely complex subject, making it difficult, if not impossible, to accurately opine on the causes of climate change let alone predict the future with a high degree of accuracy, despite rhetoric to the contrary. At the heart of the climate science debate is whether one accepts the simplistic assumption that one atmospheric element drives all of our climate change, or that the physics of climate are much more complex with interactions and feedback mechanisms making predicting the future a challenge.

A global warming timeline prepared by the American Institute of Physics marks 1800-1870 as the beginning of modern climate research. Earlier investigations of topics such as the composition of the atmosphere, the importance of the respective gases, weather readings from around the world – at least where people were and where they traveled – all contributed to the eventual evolution of climate science.

The reason why climate science starts in 1880 is its correlation to the start of the first industrial revolution, which was powered by coal and involved land clearing for greater agricultural production and the expansion of the railroads around the world, all of which contributed to faster population growth, helping boost carbon emissions. It wasn’t until 1880 that sufficient global temperature and climate data existed to begin measuring the ongoing changes. In terms of the history of the earth’s climate, 139 years is a miniscule time span relative to a planet with millions of years of climate data and thousands of years of human existence.

Working backward, global warming was the initial warning that spurred the climate change movement. Fear that we were confronting runaway temperatures, driven by increased carbon dioxide, exploded in the early 2000s. Not only was the “official” temperature data showing the planet warming – something that had been forewarned by the 1989 congressional testimony of NASA scientist James Hanson and Former Vice-President Al Gore’s 2005 book and movie, “An Inconvenient Truth” – but the U.S. Gulf Coast was devastated by Hurricane Katrina that year. It was one of 15 hurricanes that season, but only seven had been predicted. This led some climate scientists to proclaim global warming would contribute to increased tropical storm activity and storm intensity.

This is the modern temperature record. The graph shows that beginning in the late 1970s, the earth’s temperature began rising until it accelerated to the upside in recent years.

Exhibit 7. Demonstrating Global Warming

Source: icax.co.uk

What we also see is that starting in 1998, the world’s temperature ceased rising for between 10-15 years depending on measurement dates. The temperature increase hiatus happened at the same time hurricane activity was supposedly accelerating from increased global warmth. How could that be? Was it possible we were in a natural cycle for tropical storm activity?

Exhibit 8. How Temperature Data Was Changed

Source: Climatecentral.org

The temperature hiatus was demolished by people keeping track of the data claiming new, better data showed no slowdown. According to a paper in Science magazine, a second look at the global temperature data, especially that collected at sea, led to this different conclusion. The new findings showed a slight but notable increase in the average temperature challenging the 15-year global warming slowdown, which had been highlighted in the most recent UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report.

The data revision relied on new metadata, or the data behind the data, suggesting scientists weren’t properly accounting for certain types of measurements. It dealt with sea surface temperatures. Over the prior 40 years, there has been a proliferation of ocean buoys, but ships had continued their antiquated measurement techniques. The buoys, which now cover 15% of the world’s oceans, are known to have a “cold” bias compared to measurements taken from ships. That bias comes from buoy readings being taken a meter below the ocean’s surface.

For centuries, ships took sea temperatures by dropping a bucket over the side of a ship, scooping up some seawater, and dunking a thermometer in it. It became important to know what type of bucket was used, as wooden ones stayed warmer longer than uninsulated canvas ones. During World War II, an undocumented change occurred when ships started placing a thermometer near the water intake for their engines that led to a 0.6o C (1o F) increase in readings. The shift happened because it was too dangerous to use lights at night when trying to take ocean temperature readings. By the early 1960s, ocean temperatures were routinely measured by inlet-port thermometers.

Since the 1980s, sea surface temperatures are routinely collected by satellites sensing the ocean radiation in two or more wavelengths within the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum. However, temperatures are measured at the top 0.01 millimeter or less of the ocean. This makes readings susceptible to surface heating during daytimes, as well as other issues. Additionally, satellites cannot look through clouds, giving a cool bias to readings in cloudy areas.

At the time of the revision, Peter Stott, the head of climate monitoring at the U.K. Met Office [a primary temperature data collector], agreed that “The slowdown hasn’t gone away, however, the results of this study still show the warming trend over the past 15 years has been slower than previous 15-year periods.”

Was there a hiatus in the warming of the planet? An examination of land and sea temperature data shows an interesting pattern. Since the mid-1980s, land temperatures climbed faster than sea temperatures. It is noteworthy that land annual temperature averages (dots) show wide year-to-year swings. That isn’t the case for sea temperatures. The lines are 5-year weighted averages.

Exhibit 9. Land And Sea Temps Are Very Different

Source: NASA

Let’s put the current temperature data into historical perspective.

Exhibit 10. Global Warming Is Not Unusual

Source: c3headlines.com

When we examine the temperature data since the last glacial era, note how many past warm periods happened. Exhibit 10 shows a different time perspective. Immediately prior to the Little Ice Age was the Medieval Warm Period. Many of us may remember our history and literature that showed the Vikings colonizing Greenland and even reaching Canada during the Medieval Warm Period. Likewise, the Little Ice Age is memorialized in the writings of Charles Dickens and stories such as Hans Brinker, Or the Silver Skates and the frozen canals of Holland in the early 1800s. We can also think of the wintery scenes of London and Paris and the Currier & Ives portraits of New England.

Exhibit 11. Natural Forces Impact Global Warming

Source: Longrangeweather.com

The chart also shows temperatures annotated against volcanic activity, a natural climate influencer, especially for cooling the planet. It also shows many historical events matched against temperatures.

Exhibit 12. We Have Been Warmer And Cooler

Source: Wikipedia

An even longer time series of global temperature variations from the average of 1960-1990 reinforces the narrowness of temperature fluctuations for the last thousand years. The zero point on this scale is 2015. The various historical temperature series cannot be officially linked because of different definitions. As the chart’s preparer noted, temperatures in the left-hand panel are very approximate and best viewed as a qualitative indication only. Each of the panels moving leftward is expanded by an order of magnitude. The point is that the world’s temperatures have been much warmer and cooler than now. This isn’t to refute the current warming, only to demonstrate how widely historical temperatures have swung.

Understand, we are in an interglacial period, which has always been marked by rising global temperatures, and having no relationship with industry and humans. Again, this is not to denigrate the role humans have played in recent carbon emissions and their contribution to the planet’s warming. The question is whether humans are the primary source of the global warming.

Today, with modern technology, we have better temperature data. That is why global warming focuses on rising temperatures for the past 100 years. A chart showing the uncertainty about historical temperatures shows it is possible that years ago temperatures were just as high as now. That past uncertainty should always reside in the back of one’s mind when examining the climate issue.

Exhibit 13. Temperature Data Is Imprecise

Source: Wikipedia

As we know, humans have been accurately recording weather data for much longer than the 1880-2019 era used to measure temperatures. People have been measuring temperature since Galileo’s time, and the modern thermometer was invented in the early 1700s. Formal weather stations, which before the mid-1800s were mostly in Europe and the US, became ubiquitous enough by 1880 to provide an initial picture of global temperatures. That is why 1880 has become the starting point for the climate debate. Unfortunately, the vast majority of other, older climate data still isn’t digitized, which would extend our knowledge with greater accuracy.

Carbon is the target of the climatologists because it has been shown to last a long time in the atmosphere, which extends the time its greenhouse warming impact can work on global temperatures. What is often not discussed is the role of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. It is the lifeblood of the atmosphere, plant life and humans. Usually, discussions focus on greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. By that measure, CO2 represents 82% of greenhouse gases.

Exhibit 14. Outsized CO2 Role In GHG

Source: EPA

What is not appreciated is that greenhouse gases represent only 5% of the atmosphere. Water vapor is about as important a greenhouse gas as is CO2, which accounts for 3.6% of the atmosphere. Yes, it has a powerful impact on warming, but even now scientists are focusing more on methane (CH4), which lasts for only a few years, but reportedly has a 30-times greater impact on warming than CO2, but it is only a trace gas. Water vapor is also a climate influencer.

Exhibit 15. Composition Of The Atmosphere

Source: Wikipedia

A chart from the IPCC shows the history of these greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. In Exhibit 16 (next page), the red line is CO2, which was at the same peak level in 2005 as it was 120,000 years before, and about at the same point at three prior times. The blue line reflects CH4, which has a similar pattern of rising and falling as CO2, but the swings are more moderate.

Exhibit 16. History Of Greenhouse Gases

Source: American Chemical Society

One issue complicating the global warming narrative is the leading or lagging of temperatures relative to CO2. Ice cores from Greenland, the Arctic and Antarctic have been used to gain insight into that question. Initial research concluded that temperatures followed CO2 increases, but more recent studies have found that conclusion is wrong.

Exhibit 17. Ice Cores Don’t Help CO2 As Driver

Source: www.e-education.psu.edu

The Antarctic ice cores have proven to be better research tools as they have been less susceptible to melting water that can boost the CO2 concentration in the ice core. Since the beginning of the current interglacial warming period, about 17-19,000 years ago, rising temperatures preceded rising global CO2 concentrations. This contrasts with the Greenland ice core where the rise in temperatures and atmospheric CO2 concentrations coincided to within decades. An uncertainty-analysis showed that temperatures might lead CO2 by up to 21 years, while possibly CO2 leads temperatures by 24 years.

The study of ice cores has shown a “see-saw” pattern between the Northern and Southern hemispheres. As one hemisphere has warmed, the other has cooled, and vice versa with a roughly 1,500-year cycle. How this happens is likely tied to the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Cycle (AMOC), which moves water from one hemisphere to the other. AMOC brings warm southern surface waters to the North Atlantic where they become saltier and drop to the ocean floor to form the North Atlantic Deep Water, which flows south ultimately ending up in the Pacific Ocean. This see-saw pattern is demonstrated from the analysis of deep ocean cores.

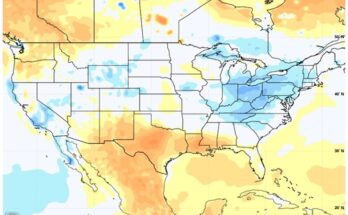

Exhibit 18. How Temperatures Are Distributed

Source: Environmentcounts.org

What this analysis shows is the climate is very complex with multiple feedback mechanisms. Factors such as sun spots, the earth’s rotation and tilt, and weather phenomenon such as El Niño and La Niña, besides clouds and volcanic activity can influence our climate and moderate or accelerate CO2’s impact on temperatures. Many of these natural events do impact global temperatures.

What is key now is to appreciate what is happening with the climate movement. It is in the midst of rebranding itself. When James Hansen spoke to Congress in 1988, the meeting room was heated overnight, so when he testified people would be sweating. Pounding the table about “global warming” was easy. Temperatures were on the rise! Dr. Hansen’s testimony helped propel the creation of the IPCC, which began with the ideological predisposition that CO2 and humans were the culprits. Its charter states: “to understanding the scientific basis of risk of human-induced climate change, its potential impacts and options for adaptation and mitigation.” Then came the warming hiatus, making it hard to push the global warming message.

The 2004-2005 period of high hurricane activity provided the opportunity to rebrand “global warming” into “climate change.” Every weather event became an opportunity to repeat the message – the earth’s warming was creating an unstable climate, which would grow worse in the future. The problem is that warming and climate were being leveraged off weather, which has its own local/regional patterns. In addition, climate change was introduced just as we entered the longest period of low hurricane activity, undercutting the climate change narrative.

Exhibit 19. Total Tropical Activity Up Recently

Source: NOAA

While NOAA shows more tropic storms and hurricanes in the 2000s, every storm is equal, even if they never threaten land. Until the era of weather satellites started in the 1960s, hurricane knowledge came from ships or islands experiencing storms as they traveled across the Atlantic Ocean from West Africa. Today, we count more tropical storms than we ever knew of before.

When the hurricane and tropic storm data is adjusted to only U.S. landfalling-hurricanes, and then just major hurricanes (Category 3-4-5), the trend has been declining since the 1900s.

Exhibit 20. Tropical Storm Activity In Downtrend

Source: University of Colorado

In recent years, the focus shifted to storm damage due to climate change. This has become a key plank for the climate change manifesto. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, 39% of the population lives directly on the coast, which represents only 10% of the United States land mass. When the distance is extended to 50 miles from the coast, over 50% of U.S. population is resident. This coastal population grew 40% between 1970 and 2010, and is projected to increase by eight more percentage points by 2020. It is the prime reason for the increase in storm damage.

Exhibit 21. Storm Damage On The Rise

Source: Aon

A 2018 paper by climate and hurricane experts at the University of Colorado showed a decline in storms since 1900. When adjusted for inflation and population growth, annual hurricane-related property damage has shown a stable trend.

Exhibit 22. Adjusted Storm Damage Has No Trend

Source: University of Colorado

Each time the global warming or climate change narratives were challenged by reports reaching contrary conclusions or pointing out flaws, there was a reaction directed at the critics. This strategy was unearthed in the 2009 Climategate scandal in which emails of scientists at the UK’s University of East Anglia, a center of early climate research, revealed how critics were denied access to scientific journals to have their critical research published. There were also discussions about techniques used to manipulate the climate data. Inquiries were undertaken by university officials and the UK government that exonerated the scientists. The quality of the investigations was questioned, however.

One focus revealed in the East Anglia emails was the temperature data analysis performed by Michael Mann. He created the infamous “hockey stick” data chart showing the acceleration in global temperatures due to global warming. What was critical for his analysis was the minimization of the Medieval Warming Period temperatures that exaggerated the warming in recent years. Dr. Mann’s statistical analysis was criticized by statistical experts and other climate scientists. This led to several high-profile legal battles. One U.S. defamation lawsuit is now in its eighth year with little progress. A think-tank involved has apologized to Dr. Mann for its commentary, but the other principals are continuing the lawsuit.

Exhibit 23. The Defamation Battle Ground

Source: principia-scientific.org

Another case involved Dr. Tim Ball, a climate scientist in Canada. A Vancouver court demanded Dr. Mann produce his data for analysis, which he refused. As a result, he was censured by the court and his research was declared to be unusable by future climate scientists.

Another climate science battle was waged over Mr. Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth” film. The British Government had distributed the film to schools with accompanying Guidance Notes to Teachers. A legal action was brought by New Party member Stewart Dimmock for the misleading claims in the movie. The British court, after extensive investigation, ruled the film to be misleading in nine respects. The court directed the Guidance Notes be amended to make clear that the film was a “political work” and promotes only one side of the argument. The nine inaccuracies of the film were to be highlighted for school children, and if the teachers fail to do so, they could be in violation of the Education Act of 1996 and guilty of political indoctrination.

There were also egregious attacks on climate scientist Roger Pielke, Jr. of the University of Colorado. The intensity of the attacks caused Dr. Pielke to give up climate research. He recently returned to the climate research arena and talked about his ordeal. His research focus is on climate and disasters. If you Google Dr. Pielke, you will find many of the attacks, which he rebutted with documented facts in a 64-tweet presentation.

Since Dr. Pielke did not sign on to the climate change science and damage claims, he was attacked by not only the climate science community, but also by political operatives (Center for American Progress founded by John Podesta, as well as billionaire Tom Steyer). It cost him a staff writer position with Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight web site, as well being labeled a “climate denier” by Foreign Policy magazine. After testifying before Congress, he was attacked by President Barack Obama’s science advisor John Holdren, and investigated by Arizona Representative Raul Grijalva (D), which included erroneous claims that he was funded by Exxon Mobil Corp. (XOM-NYSE).

In 2006 in the run up to the IPCC AR4 report, Mr. Pielke helped organize an international workshop in partnership with global insurance giant MunichRe in Hohenkammer, Germany. The plan was for the 32 participants from 16 countries to review the 24 commissioned background papers and reach a consensus. The workshop summary was published in Science. It concluded:

Exhibit 24. Climate Storm Damage Conclusion

Source: Roger Pielke, Jr.

The following year, Dr. Pielke turned to Section "1.3.8.5 Summary of disasters and hazards" in the IPCC AR4 2007 report, only to see it had relied on one study, and included a graph showing a link between the climate anomalies and disaster costs. The report cited a paper by Robert Muir-Wood and others. He was one of the workshop participants and the study had been commissioned. The cited paper was mis-identified to appear to have been published prior to the cutoff date for inclusion in the IPCC report.

When published, the paper did not include the graph or the underlying data, but importantly, it contradicted the conclusion published in the IPCC report! In February 2010, during a public debate at the Royal Institution in London, Mr. Muir-Wood revealed he had created the graph, included it in the IPCC report, and then intentionally miscited it in order to circumvent the IPCC publication deadline. He acknowledged that the graph should not have been included in the report. His employer in 2006 predicted the risk of U.S. hurricane damages had increased 40%, necessitating higher insurance premiums equal to $82 billion according to the Sarasota Herald Tribune.

What we have is a clear example of climate scientists working to circumvent honest science investigation and distorting significant climate documents. The IPCC report is noted for its scope and the use of a summary report written by non-scientists for public and political consumption, while releasing the backup data and analysis much later. The summary report has often reported different conclusions, or emphasized the most extreme model predictions to hype the fear of climate change’s impact.

While Dr. Pielke’s experience is extreme, his honesty in testifying about the uncertainty of climate research conclusions was disconcerting for those with an agenda. Therefore, as his profile was growing, especially with the FiveThirtyEight position, he needed to be destroyed. The uncertainty about the climate science had been demonstrated by the inability of climate models to accurately recreate past climate. Critically, the models are based on CO2 as the primary driver of rising temperatures. However, these climate models admit they can’t deal with clouds and other natural weather events. They are improving, but they remain the foundation for the radical economic and societal restructuring being mandated to address climate change.

Exhibit 25. Climate Models Very Wrong

Source: John Christy

Climate scientist John Christy showed how far the temperature forecasts of the 44 climate models employed by the IPCC were from reality. The realization of the shortfalls of climate models has filtered into the IPCC by its scaling back temperature projections in the AR5 2013 report. This forecast is a far cry from Dr. Hansen’s projection of a 1o C rise every 20 years until 2050 in his congressional testimony. His forecast called for a 6o C increase.

Exhibit 26. IPCC Has Lowered Temperature Forecast

Source: Christopher Monckton

As the public learns of the costs and disruptions they face while attempting to meet the IPCC’s CO2 goal to limit temperature’s rise, they are dismayed. The climate media likes to point to the growing concern of Americans and voters to climate issues. Adaptability to higher temperatures is never considered an option. The data, however, shows more deaths result from cold than heat. The mandates ignore the U.S. success in reducing carbon emissions by switching from coal to natural gas for generating electricity.

Determining public attitudes by polls depends on how questions are posed. If climate/environment concern is questioned, Americans worry. But if asked to list their top concerns, climate/environment hardly registers. This disparity necessitates hitting the mule with a 2×4, which is behind the “climate emergency” narrative. It also underlies the effort to enlist our youth as agents for change. Is there a more susceptible group for manipulation?

Attacking critics and promoting false narratives has been a hallmark of extreme climatologists. Using “emergency” is designed to pressure people to act, maybe without questioning the science or the alternatives for a cleaner world. Calling it an “existential threat” furthers the urgency argument for motivating politicians to curb fossil fuel use regardless of the economic and social harm the policies cause, or even considering the possibility it can happen. Banning scientists with different data or conclusions from speaking is another example of the fear of an honest debate over climate science.

European environmental parties won greater representation in their various elections this year, however, the European Union has failed to adopt more stringent emission reduction targets. The public is waking up to the costs of climate mandates, especially in Europe. We are early into the climate emergency rebranding, and with a U.S. election scheduled for next year, expect to be treated to non-stop climate disaster articles, rhetoric and rallies for the next 15 months. Climate mandates are an existential threat to the energy business and its executives must be alert.

Alice, The Electric Plane, Was A Hit At Paris Air Show (Top)

The recent air show in Paris drew substantial media attention because of the concerns over the grounding of Boeing Company’s (BA-NYSE) 737 MAX following a second air crash. The apparent mismanagement of the plane’s release and pilot training to deal with certain operating peculiarities had led to plane order cancellations and questions about the company’s future sales. The media was also focusing on the “flight-shaming” movement on social media, especially given the Green New Deal’s demands for a net-zero carbon emissions world. Alice, the electric plane, may be part of the answer.

Exhibit 27. Electric Plane Alice Prototype

Source: AP

According to environmentalists, air transportation is the most perplexing challenge to decarbonize the world’s economy. Global air transportation currently accounts for 2% of the world’s total carbon emissions. It experienced significant growth in 2018 as data from Rhodium indicates. The issue is figuring out how to reduce air transportation emissions in a world where air transport is growing rapidly. Airlines carried 4.3 billion passengers worldwide in 2018, an increase of 38 million from 2017. The International Civil Aviation Organization estimates that by 2020, global international aviation emissions will be 70% greater than in 2005. By the middle of the century, emissions may increase by upwards of 700%. How to reduce emissions is the challenge, without stopping people from traveling.

Exhibit 28. Cars Are Not Driving U.S. Emissions

Source: Axios

The solution for all other transportation emissions is the use of electric power – cars, trucks, buses, trains, and even ships. Planes present a significant challenge because batteries add substantial weight to the plane and don’t last long enough for great distances. Some aircraft manufacturers are considering hybrid planes with electric engines and fuel tanks. The airlines are also experimenting with biofuels to reduce their carbon footprints, but the costs remain a significant hurdle.

Israeli startup Eviation introduced Alice, a battery-powered, nine-seater plane at the air show. The plane can fly 650 miles at 10,000 feet at a speed of 276 miles per hour on a single battery charge. The $4 million plane is targeting its first test flight later this year with U.S. certification by 2022. Cape Air, a New England regional airline, has taken an option on 20 of the Alice planes. Many of the airline’s routes are extremely short, such as Westerly, Rhode Island to Block Island, about 13 miles away. Maybe in a few years, the planes flying over our summer home will be silent.

Can America’s Team Score Big In The Natural Gas Market? (Top)

A few weeks ago, Comstock Resources Inc. (CRK-NYSE) shocked the energy world with its announcement of the purchase of privately-owned Covey Park Energy LLC in a cash-and-stock deal valued at $2.2 billion. The deal propels Comstock into the leading position in the natural-gas-dominated Haynesville basin, which seems to be experiencing a revival. Who in their right mind would load up on natural gas producing assets while prices are flirting with $2 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf), the lowest they’ve been for three years? It has to be someone with a vision for a brighter natural gas future, and especially someone in a financially-strong position who could sustain the strain from lower gas prices. That man appears to be Jerral Wayne (Jerry) Jones, owner of the Dallas Cowboys – America’s Team.

Mr. Jones publicly equated the Covey Park deal with his purchase of the Dallas Cowboys’ National Football League franchise some 30 years earlier. Looking back on the history of that investment may provide some perspective on what might happen to natural gas in the future. That said, we always keep in mind that past performance is not an indicator of future success.

In January 1989, Mr. Jones cut a deal with the Dallas team’s owner, H. R. (Bum) Bright, to buy the team for a record $140 million, $65 million for the team and $75 million for the stadium. This was the first time any professional sports team had changed hands at a value in excess of $100 million. And that was for a team who had finished the prior season with a 3-13 record and was hemorrhaging cash at the rate of $1 million per month and likely headed toward bankruptcy. Five years earlier, Mr. Bright, along with 11 limited partners, had purchased the Cowboys from its founder Clint Murchison, Jr. for $85 million. The team succeeded the first year of Mr. Bright’s ownership by finishing with a 10-6 record and making the playoffs. It subsequently fell to 7-9 and 7-8 records before its dismal performance the year prior to the sale to Mr. Jones.

According to media stories, Donald Trump had tried to buy the Cowboys two years earlier for $50 million, and described the Jones purchase as “a bad deal.” Even Mr. Jones’ accountants and lawyers were advising against the deal, as the Cowboys were losing money and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) had already foreclosed on 13% of the team’s ownership and was heading to court on an additional 40% – all stemming from the savings and loan financial crisis. The advisors reportedly said the team was worth $60 million, yet Mr. Jones prepared to offer over double that price.

When the financial discussions got down to the final stage, the two parties were close but not in complete agreement. Mr. Bright told Mr. Jones he needed a final offer by the next day. Mr. Jones finally put his offer on stationary from his hotel room at the Mansion on Turtle Creek, but spent a sleepless night worrying about his bid. He thought he had a number that would satisfy Mr. Bright. It turned out the two sides were $300,000 apart. Mr. Bright reportedly took out a quarter and said “let’s flip for it.” Mr. Jones lost.

Dallas Cowboys fans were introduced to the brash Arkansas Razorbacks’ football co-captain of its 1964 national championship football team at a strange Saturday night press conference in late February at the team’s Valley Ranch headquarters. He told the reporters that earlier he had fired Tom Landry, the only coach the Cowboys had for 29 years. He also announced he would be bringing in his former University of Arkansas football teammate and University of Miami coach Jimmy Johnson with no NFL experience to replace Mr. Landry.

In addition, Mr. Jones stated he would be in charge of every detail related to operating the franchise, down to “jocks” and “socks.” It appeared he was about to become the NFL’s equivalent to the dominating oil man J.R Ewing from the iconic blockbuster TV hit “Dallas.”

After a dismal 1-15 season in his first year of ownership, Mr. Jones’ Cowboys won three Super Bowl championships within the following five years. Since then, the Cowboys have never been back to the Super Bowl. While his football team’s success has been disappointing since those early years, Mr. Jones has been able to grow the value of the franchise, recognized as the most valuable profession sports franchise by Forbes magazine. Up until the early 2000s, the Cowboys were reportedly worth about 20-30% more than the average NFL franchise. Since 2005, the value gap has widened as the Cowboys’ value has grown considerably faster than that of the average of other NFL franchises.

Exhibit 29. Dallas Cowboys Most Valuable Franchise

Source: Business Insider

Some of that franchise value increase – as well as for every other NFL team – is due to Mr. Jones leading a rebellion of the younger team owners in the mid-1990s over proposed changes the league’s television contract with CBS Broadcasting. Shortly after Mr. Jones had bought the Cowboys, he learned that the latest league broadcast contract kept payments to the teams flat with its prior deal. The new contract called for a cut in the broadcast payments, something the younger owners fought and reversed.

Besides TV revenues, the Cowboys’ stadium makes a lot of money, and the team has leveraged its brand in many ways to drive the team’s value to over $5 billion today. This value creation record may have energy investors wondering what Mr. Jones sees about natural gas that attracted him to the Comstock deal, and now the Covey Park purchase. Can he repeat this magic? So far, it doesn’t seem to be working as demonstrated by the stock chart for Comstock since Mr. Jones became involved. The $7 per share price was the agreed price for the 88.6 million new shares Mr. Jones received for his sale of oil and gas properties in North Dakota. The shares gave Mr. Jones an 84% interest in Comstock.

Exhibit 30. Comstock Reflects Gas Oversupply

Source: Bloomberg

With the Covey Park deal, Comstock becomes the leader in the Haynesville gas basin, once thought to be the biggest gas basin the nation, but which proved much more challenging to develop profitably. Over the years, Comstock’s engineers have worked successfully to reduce the breakeven cost in the field. Based on the company’s investor presentation to analysts about the Covey Park deal, the pro forma company will have net production of over 1.1 billion cubic feet equivalent. It will own 290,000 net acres in the Haynesville/Bossier play, with 94% held by production, an average working interest of 74%, and 5.4 trillion cubic feet equivalent of SEC proved reserves. Comstock will have over 2,000 drilling locations, equal to over 20 years of drilling activity. Importantly, the unit production cost is estimated at $0.76/Mcf, and Comstock expects to fund drilling within operating cash flow of the new company.

Many investors are probably not familiar with Mr. Jones earlier involvement and success in oil and gas. That successful history provided Mr. Jones with the money to purchase the Cowboys. This interesting history demonstrates, as is often true in business, that it isn’t what you know but rather who you know. We met Mr. Jones before he became wealthy, but the friendship that ultimately made him wealthy was evident. At the time, Mr. Jones was a small oil and gas producer, but becoming a more important player in the evolution of Arkla, Inc., a natural gas transmission, distribution, and exploration and production. The key friendship was with Sheffield Nelson, the man running the Shreveport, Louisiana based company. Arkla’s history is a microcosm of the evolution of the natural gas industry during the 1970s to 1990s, a tumultuous period in the history of the energy industry.

Arkla’s predecessor, Southern Cities Distributing Company, incorporated in 1928. In 1934, it merged with Arkansas Louisiana Pipeline Company, Reserve Natural Gas Company, Arkansas Natural Gas Company, and Public Utilities Company of Arkansas to form the Arkansas Louisiana Gas Company, a subsidiary of Cities Service Company. The Securities and Exchange Commission in 1944, under the Public Utility Holding Company Act, required the company’s divesture from Cities Service. Hearings and litigation delayed the divesture for eight years, after which Arkla was listed on the American Stock Exchange. Two years later, Wilton (Witt) Stephens acquired a controlling stock interest, becoming a director two years after the acquisition. In 1957 he became board chairman and the company’s president a year later. Mr. Stephens owned an investment bank, Stephens, Inc., and was a dominant figure in Arkansas business and politics.

Mr. Stephens began to “conglomerate” Arkla with acquisitions of an air conditioning equipment manufacturer, a finance company for appliances and construction, fertilizer and plywood manufacturers, a cement company, and even an amusement park. Later, Arkla acquired gas distribution companies and the gas production assets of Southwest Natural Gas Company. The gas reserves and production in Louisiana proved inadequate, so the company expanded E&P operations into Oklahoma, including building a pipeline from the company’s gas operations in Arkansas and the new producing wells.

The 1970s were chaotic for the natural gas industry, as price controls on production dedicated to interstate pipelines was not competitive with intrastate gas pipeline who could pay substantially higher prices. Arkla worked to build up its E&P, which actually became so successful that it had more supply than it needed. At this point, Arkla was being headed by Sheffield Nelson, a protégé of Witt Stephens. A key to Arkla’s oil and gas reserve success was teaming up with independent producers, one of whom happened to be Jerry Jones, who was active in the Arkoma basin (spanning the southeast corner of Oklahoma and the northwest corner of Arkansas) where Arkla had its leases. The company needed more production as it signed a contract in 1981 to sell natural gas to Central Louisiana Electric Company (CLECO).

To improve its oil and gas operations, on New Year’s Eve of 1982, the Arkla board approved the sale of leases on almost 15,000 acres to Mr. Jones’ drilling company for $15 million. At that time, within the Arkoma basin, gas acreage had been auctioned for $2 million for 640-acre sections, or the equivalent of $45 million for the 15,000 acres. In addition, Arkla agreed to match all of Mr. Jones’ company’s drilling costs dollar for dollar up to $10 million a year on the acreage, spending about 12% of Arkla’s annual drilling budget. Arkla agreed to buy the gas output for $3.40 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf) for wells costing $300,000 to $500,000 to drill. Lastly, Arkla agreed to finance $11.25 million of the $15 million purchase price at 10% annually, at a time when the bank prime rate was two percent higher, and Arkansas banks charged its best customers 13.5%.

The final conflicting part of the transaction was that the Arkla acreage Mr. Jones was acquiring represented the company’s half-interest in the Cecil and Aetna fields in the basin. The other half-interest in the Cecil field was owned by Mr. Stephens with the gas dedicated under a long-term, low-price contract of $0.55/Mcf. The Stephens company was also a participant in the Aetna field along with a subsidiary of Exxon, Continental Oil (Conoco), and Union Life Insurance Company, owned by Ray Hunt, the son of H.L. Hunt. These other participants had a right of first refusal on the Arkla acreage, yet none of them offered to buy the leases or sell their interest. What Mr. Jones had agreed to was to sell Arkla gas from his other 100,000 acres, plus if Arkla needed it, he would commit gas production from leases he acquires over the next five years in five states – Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. The other lease owners understood this agreement was something they couldn’t match, acknowledging the power of the special friendship between Mr. Nelson and Mr. Jones.

Shortly after the deal was agreed, Mr. Jones was appointed to the Arkla board of directors, which would help ensure that all his gas was purchased by the company. There is also speculation that Mr. Jones convinced Mr. Stephens to give up some interests in return for better pricing on gas he could not sell to Arkla due to the old contract and the intractable personal/political problems developing between Mr. Stephens and Mr. Nelson. No one knows the details.

As the natural gas market evolved, eventually it became more important for Arkla to buy its way out of the agreement with Mr. Jones company. He and his partner sold the production, leases and acreage for $175 million. That money ($90 million) was the source of his funds to buy the Cowboys. So, from a $15 million investment, Mr. Jones has parlayed his gas investment into a net worth in excess of $5 billion, of which the Cowboys represents most of the value. Now, he is back in the oil and gas business with control of Comstock, and now Covey Park, a highly successful E&P company. Will Mr. Jones be able to parlay his investment in Comstock and natural gas, which after the Covey Park deal and the additional capital he is investing in the transaction, worth $1.1 billion, into another America’s Team success?

Contact PPHB:

1900 St. James Place, Suite 125

Houston, Texas 77056

Main Tel: (713) 621-8100

Main Fax: (713) 621-8166

www.pphb.com

Parks Paton Hoepfl & Brown is an independent investment banking firm providing financial advisory services, including merger and acquisition and capital raising assistance, exclusively to clients in the energy service industry.