Energy Musings contains articles and analyses dealing with important issues and developments within the energy industry, including historical perspective, with potentially significant implications for executives planning their companies’ future.

Download the PDF

April 28, 2023

Bananas, Kumquats, and Today’s Inflation Problem

Many investors believe inflation is on the run and soon will return to pre-pandemic lows. There is a history of head fakes about inflation that needs to be examined. READ MORE

Bananas, Kumquats, and Today’s Inflation Problem

Cornell University economist Alfred Kahn, President Jimmy Carter’s advisor on inflation and chair of the Council on Wage and Price Controls, was famous for talking about recessions and depressions as necessary to win the battle with the raging inflation of the 1970s. He was chastised for using such scary language – remember we were not far removed from the Great Depression. Kahn switched to calling them bananas until a banana company took offense and he changed to kumquats. Who knew what a kumquat was?

Politicians in Washington hate talking about recessions, let alone depressions. But if inflation does not retreat to the Federal Reserve’s 2% target rate, people will continue suffering. The good news: the March Consumer Price Index (CPI) for all items posted an increase of 5.0%, the smallest monthly rise since May 2021. Energy falling 6.4% helped, with gasoline falling 17.4%, although electricity rose 10.2%. Fortunately, the latter counts less in the index than the former.

In the 1970s when the CPI was rising by 15%, Arthur Burns, chair of the Federal Reserve, asked his economists to develop an index that was less politically sensitive. They came up with Core CPI which strips out the volatile food and energy components. In March, however, Core CPI increased by 5.6%, largely attributed to an 8.2% increase in housing that represented over 60% of the total increase. So much for getting rid of the volatile categories. Compared to expectations, the March CPI was slightly better while Core CPI was slightly worse. Good news or bad?

On the bad side, since March 2021, the CPI has increased by 14.0% driven by food prices climbing 18.0% and energy soaring 23.6%. Without those categories, Core CPI was 12.4% higher – better but not by much. For consumers, food and fuel claim significant shares of people’s budgets but so do housing, autos, and health care expenses. Inflation hurts, no matter who you are.

Despite Main Street’s suffering, Wall Street cheered the CPI report. Investment managers and CNBC talking heads rejoiced at the lower rate declaring the “end of inflation!” They called the CPI’s steady decline since peaking at 9.1% last June a victory. For them, the CPI is heading directly to the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target. The stock market will soar. Break out the champagne!

At What Cost?

Two days later, BlackRock’s CEO Larry Fink appeared on CNBC and threw cold water on the lower inflation enthusiasm. Fink said the Russian invasion of Ukraine had accelerated the shift away from globalization. Additionally, the United States has embarked on an industrial policy that has us “reshoring” or “nearshoring” our supply chains. These moves will be inflationary.

An expanded U.S. manufacturing base will see more products made here. The electric vehicle (EV) industry is Exhibit No. 1. Its growth is driven by mandates, tax credits, and subsidies. Government largess can only be earned if a major portion of an EV is built in the U.S. with American or North American manufactured components.

One outcome of “reshoring” is that global trade will shrink as fewer goods are imported and more are manufactured here. Fink, who has been a long-time promoter of globalization, said he was not making a value judgment on the industrial policy, but asked, “At what cost?” A clue was in Fink’s March letter to BlackRock shareholders.

And while dependence on Russian energy is in the spotlight, companies and governments will also be looking more broadly at their dependencies on other nations. This may lead companies to onshore or nearshore more of their operations, resulting in a faster pullback from some countries. Others – like Mexico, Brazil, the United States, or manufacturing hubs in Southeast Asia – could stand to benefit. This decoupling will inevitably create challenges for companies, including higher costs and margin pressures. While companies’ and consumers’ balance sheets are strong today, giving them more of a cushion to weather these difficulties, a large-scale reorientation of supply chains will inherently be inflationary.

Oops, that inflation argument again. A recent Wall Street Journal article on automotive parts supplier Premium Guard Inc.’s decision to build a factory in Mexico to avoid supply chain issues points out the challenges of nearshoring. The range of raw materials available in Mexico is more limited and expensive than in China. However, Mexico’s labor is cheaper than in the U.S., but more costly than in Asia. The latest North American Free Trade Agreement provides greater unionization benefits for Mexican labor that could boost the country’s labor costs or produce disruptions from strikes. Shipping distances are shorter and fewer tariffs are imposed, which lowers costs and speeds up delivery times. But Mexico’s electrical grid can be unreliable, and the country lacks sufficient raw materials and locally produced parts that force manufacturers to continue sourcing components from Asia.

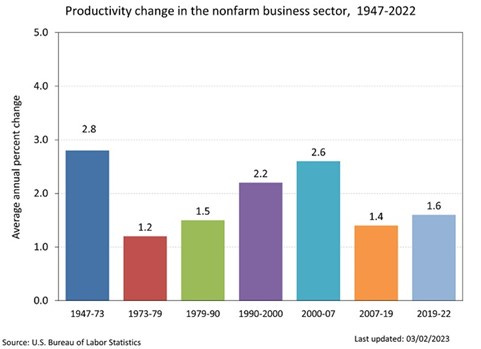

Fink noted other factors that could impact inflation – productivity and interest rates. The chart below shows U.S. nonfarm productivity by eras for 1947-2022. Note how the low productivity rates of 2007-2022 were like those during the 1973-1990 era when inflation was soaring, and the U.S. was battling to control it and its fallout. Fink asked, “Where are we going to see the boost in productivity? Because if we don’t, that’s going to be another reason why we’re going to have a stickier inflation.”

Exhibit 1.

The history of U.S. labor productivity shows the last 15 years have seen a rate of improvement similar to what was experienced in the 1970s. (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Fink pointed out that in the new era of “higher for longer” interest rates, investors can earn 5%-6% returns on bonds, up from 1% not long ago. This means pension funds can earn a substantial portion of their target returns without having to risk substantial sums in the equity market. Fink said many of BlackRock’s clients are “lowering their risk” as a result, which may explain why the stock market is laboring to rise. Higher interest rates, however, will cost families, businesses, and governments, pushing up inflation. How aggressively central banks can fight inflation with higher rates is the challenge. Fink wrote:

Central banks are weighing difficult decisions about how fast to raise rates. They face a dilemma they haven’t faced in decades, which has been worsened by geopolitical conflict and the resulting energy shocks. Central banks must choose whether to live with higher inflation or slow economic activity and employment to lower inflation quickly.

These issues lead Fink to see inflation remaining higher than others and being stickier. As Fink told CNBC: “I think we’re going to have a 4-ish percent floor in inflation.” That would be twice the Federal Reserve’s target, which will make the battle to control inflation much more challenging. It will take longer than expected to bring down, or the Fed will capitulate and accept a higher sustained inflation rate than market optimists expect. Such a scenario is receiving little consideration from investors, business leaders, and government policymakers. Ignorance is bliss in today’s world.

Inflation Is Dead – Or Is It?

Those arguing that inflation is dead say the Federal Reserve Board should stop its rate hikes and start cutting them to mitigate a severe economic contraction. They worry that the recent banking crisis in the U.S. and Europe has us on the cusp of another global financial crisis. While that may be the focus of investors, several influential geostrategists are talking about a more momentous shift upcoming. We will get to that aspect later. First, we turn to the Fed, interest rates, and inflation.

In 2020, the pandemic exploded, and economies were shut down to prevent the spread of the deadly virus. Governments and central bankers rushed to provide financial support for their citizens who lost their jobs and incomes due to the shutdown policies. Although the cash provided near-term support for families, businesses, and local governments, for many it was just extra money, so it went into savings. When the shutdowns ended, not surprisingly economic activity rebounded – much sooner, faster, and stronger than anticipated. Driven by savings, the demand for goods far outstripped the capacity of global supply chains. Strong demand, supply shortages, and bottlenecks pushed prices up – the economy’s way to ration output.

As inflation climbed, governments and central banks viewed the price hikes as temporary. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and his predecessor Janet Yellen, currently U.S. Treasury Secretary, seconded that view. Printing presses continued pumping out money as politicians saw it as their role to make sure people were well cared for, even if emergency funds were not being spent, or even appeared needed. In Europe and Canada, officials followed the U.S. lead. Thus, it was nearly a year after inflation became evident that central banks began fighting it by raising interest rates. Once the rate hikes began, the banks became aggressive as inflation accelerated. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve first increased rates in March 2022 following four years of no movement. The first increase was a quarter of one percentage point, lifting the Federal Funds rate into the range of 0.25-0.50%! That hike was to be followed by six more in 2022.

Today, the federal funds’ target rate is 4.75% – 5.00%, with expectations it will be boosted to 5.00% – 5.25% at the Federal Reserve’s May meeting. The average annualized inflation rate for the first three months of 2023 was 5.8%, meaning real interest rates remain negative by 1%. Some economists suggest that investments need to earn a positive real return, so the Federal Reserve should raise rates above 6%. If inflation continues to decline, this argument may weaken and be overwhelmed by growing fears of a recession.

The dilemma facing the Federal Reserve is how high to raise interest rates to tame inflation, its primary policy role. Investors worry rates are too high and as inflation deflates, we could be facing another banking crisis, as well as propel the economy into a serious recession with dire employment consequences. At the same time, investors such as Larry Fink worry that our newly adopted industrial policy will embed a higher inflation rate into the economy than the current 10-year inflation expectation of a 2.1% rate.

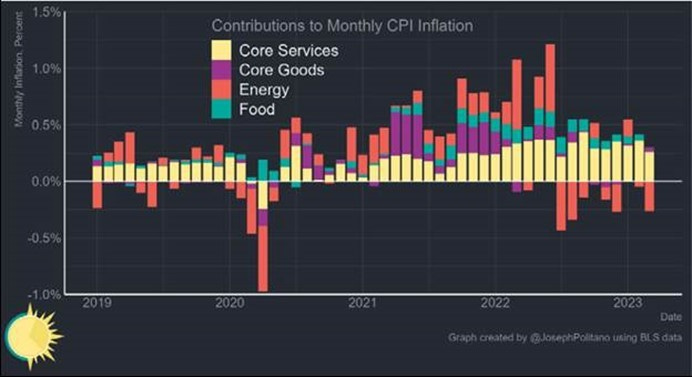

Exhibit 2.

Service inflation has come to dominate the CPI since mid-2022 but will goods become more of an inflation force as during 2021? (Mauldin Economics)

The driver of inflation is shifting from goods to services. There is much less room to moderate service inflation because they are human-related and less impacted by productivity improvement. For example, healthcare costs were predicted to ease if electronic medical records were adopted. Doctors tell us they now spend more time filling out computer databases than seeing patients – the exact opposite of what was predicted.

Service costs are highly sensitive to labor market conditions. Despite slowing economies, unemployment rates remain at record lows. Inflation is creating labor market troubles. Skilled workers are in short supply, pushing up wages and costs associated with their work. Low-earning employees are demanding higher wages, as well as unionized workers. Health workers in the U.K. are on strike. Government workers across Canada are striking for higher pay to offset the inflation they suffered. U.S. railroad unions negotiated a 24% pay raise over 2020-2024 with an immediate $16,000 payout to workers. Even retired workers – Social Security – received an 8%+ increase this year and are expected to receive another hefty increase in 2024. These wage increases pressure business costs that will be recovered in higher prices, such as Procter & Gamble’s recent announcement it raised prices by 10% across its consumer brands for the second consecutive quarter to preserve its profit margins.

Consumer Struggles With Inflation

Another troubling sign of inflation’s damage is the shocking rise in consumer debt. According to WalletHub’s Credit Card Debt Study, consumers added $180.2 billion in credit card debt during 2022, which compares with the average annual increase over the past 12 years of just $47.8 billion. In the fourth quarter, credit card debt rose by $85.8 billion, the biggest quarterly increase recorded to date. Along with rising consumer debt, so too are delinquencies. That reflects consumers struggling with higher costs and stagnant wages. Rising interest expenses on credit card debt will further hurt consumers. One estimate is that consumers will face an additional $3.4 billion in interest expenses in 2023.

“Credit card balances are forecast to rise over the course of the year as many consumers continue to turn to cards to help them manage cash flows,” said Paul Siegfried, senior vice president and credit card business leader at credit reporting firm TransUnion. He went on to say, “We expect card delinquency to increase in 2023 as consumers face liquidity shortages from the prolonged high inflation environment, slowing wage growth, and expected increases in unemployment.”

Consumers also face rising energy costs to power and heat their homes. Energy poverty is when a family devotes a significant share of its income to energy bills. A 2023 study by an international group of scientists published in Nature Energy estimates an additional 78-141 million people worldwide could be pushed into extreme poverty by high energy bills. According to Eurostat, 35 million Europeans or 8% of its population were in energy poverty in 2021, before soaring energy prices last year slammed consumer budgets. A World Economic Forum study released last January predicted that high energy and food prices could last for two years. Thus, there is plenty of evidence that inflation for whatever reason is hurting people everywhere.

We have written about the need for inland maritime shipping rates to rise by 30% or more before the industry can justify adding new capacity at a time when new shipping routes and new markets are keeping vessel fleets fully utilized. Furthermore, a lack of drivers and higher fuel bills are pushing up road transportation costs, which impacts all consumer purchases.

While investors are sanguine about falling inflation, maybe they should consider the history of prior periods of accelerating inflation. A chart of the CPI for all items and Core CPI from 1965 to 2023 highlights the experience of inflation in the 1970s and the 2000s. Current inflation rates are above those experienced in the 2000s, but well below those of the 1970s. The concept of Core CPI was born from the experience of the 1970s. The red line (Core CPI) on the chart seldom exceeds the CPI number except when oil prices collapse such as in 1983, 1986, 2009, 2015, and 2020.

Exhibit 3.

Core CPI (without energy and food) closely tracks the overall CPI except when oil prices experience a price disruption. (St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank)

Each peak in the CPI and Core CPI is slightly ahead of or in sync with recessions (gray bars). In the 1970s and 2000s, each time inflation seemed to be ending, there was another spike. In both eras, the second spike resulted from the early abandonment of tight monetary policy for fighting inflation (hiking interest rates) to easing money to fight recessions. To us, the recent rhetoric from the various governors of the Federal Reserve about slowing or stopping the current interest rate hikes, even with inflation well above their 2% target, and even hinting they will be cutting rates before year-end to help the economy deal with the anticipated recession is setting us up for another bout of inflation in 2024 or later. This is supportive of Larry Fink’s view of a higher and stickier inflation rate.

A Great Reset In The Works?

A jump in inflation in 2024 will coincide with the next presidential election. Will a sitting president allow that to happen as he enters the campaign? No. A sitting president will use every lever at his disposal to keep interest rates down, employment up, and handouts going to ease the pain of inflation. That will postpone the war on inflation and allow for it to fester further in the economy. The 2024 election has become a marker in the thinking of two noted geostrategists about the future trajectory of our society, economy, and democracy, all of which will be impacted by higher-than-anticipated inflation. George Friedman of GPF Geopolitical Futures and Neil Howe with the Center for Strategic and International Studies have both recently focused on today’s turmoil in society and the economy and the implication for a dramatic change soon. Both strategists utilize generational cycles and their past impact on the world for guidance in the future.

Friedman, in several articles and a recent webinar, is updating his timing for the dramatic change he outlined in his 2020 book “The Storm Before The Calm.” In his book, Friedman identified the 2028 presidential election, the last before the 2030s, as the pivotal one for America. Now he thinks it may be the 2024 election.

Friedman began his book with a comment about the rabid support and hate of Trump, “as if he alone were the problem or the solution.” Friedman went on to write:

There is nothing new about this. The kind of mutual rage and division we see in America today is trivial compared with other times in U.S. history – the Civil War, in which 650,000 died, or the 1960s, when the Eight-Second Airborne was deployed to fight snipers in Detroit.

As the various generational cycles – social, economic, political, and institutional – come into sync in the near term, a new America will emerge. Friedman points out that there have been two major American cycles in our history – the institutional cycle that transpires about every 80 years, and the socioeconomic cycle that occurs approximately every 50 years. The first institutional cycle began with the Revolutionary War and the drafting of the Constitution in the mid-1780s and ended with the Civil War in 1865. The second cycle ended about 80 years later with World War II. Eighty years later is about now.

The socioeconomic cycles changed in the 1880s when the country refocused after the Civil War, and then again in the 1930s with the Great Depression. The last shift was in the 1980s when the social and economic dysfunctions that began in the late 1960s produced a fundamental shift in how the economic and social systems functioned. Think of the battle against inflation then and the economic and social fallout compared to today’s inflation fight.

For Friedman, the institutional and socioeconomic cycles are coming to their ends at roughly the same time. This is a rare occurrence and suggests a more violent adjustment for America. One could argue that our current economic problems and the contentious societal and political conditions could trigger a historical readjustment.

During the 1970s inflation era, while Federal Reserve chair Paul Volker received most of the attention because of his interest rate moves, an equally significant Washington player was Kahn, the Cornell University professor who specialized in regulated industries. He was picked by President Jimmy Carter in 1977 to head the Civil Aeronautics Board (now defunct) that regulated the airlines. He was instrumental in garnering the support needed for federal legislation to deregulate the airline industry – the first thorough dismantling of a comprehensive system of government control since 1935. Airline deregulation became the template for deregulating the trucking and rail industries, saving consumers untold amounts of money over the years.

At the end of 1978, Carter picked Kahn as his inflation advisor which led to the bananas and kumquat language. While Volker was fighting inflation aggressively with interest rates, Kahn was attacking inflation by dismantling barriers that kept airline and other transportation prices high. Beginning in the 1980s, decontrol helped reduce the embedded inflation from inefficiencies in large and systemically important industries in the nation’s economy. Could we have another economic revolution in the future?

Howe has also authored a recent article based on his upcoming book “The Fourth Turning Is Here” which focuses on how America is changing and will change further in the coming years. He sees a similar tumultuous period for America as Friedman, but his driving forces are slightly different. Howe considers the economic, social, political, and generational tumult unfolding not just in the U.S. but around the world. He is not sure what will trigger the crisis that will lead to the new America, but he is an optimist about its long-term future, just as is Friedman. Demographics have been one of Howe’s drivers of economic, political, and social change, and America is certainly experiencing significant change on that front. Howe concluded his article:

In the face of adversity, the old America is disintegrating. But at the same time, America is moving into a phase transition, a critical discontinuity, in which all the dysfunctional pieces of the old regime will be reintegrated in ways we can hardly now imagine.

The civic vacuum will be filled. Welcome to the early and awkward emergence of the next American republic.

Fink, Friedman, and Howe all see a tumultuous near-term future for America. Reaction to inflation is a sign of this tumult, as are the toxic social and political debates. All three strategists are hopeful that the long-term future for America will be considerably better than its recent past, and certainly its current condition. The challenge will be surviving this tumultuous period that will become worse before it gets better.

Contact Allen Brooks:

gallenbrooks@gmail.com

www.energy-musings.com

EnergyMusings.substack.com