- "Houston, We’ve Had A Problem" Do We Recognize It?

- Eni CEO Explains High World Oil Prices

- Seems Like Old Times Again – Look Out!

- Are Venture Capital Pros" Concerns True for Energy?

- For Energy Speculators: 2006 Hurricane Season a Bust

- The New Oil Sands Business Model?

Note: Musings from the Oil Patch reflects an eclectic collection of stories and analyses dealing with issues and developments within the energy industry that I feel have potentially significant implications for executives operating oilfield service companies. The newsletter currently anticipates a semi-monthly publishing schedule, but periodically the event and news flow may dictate a more frequent schedule. As always, I welcome your comments and observations. Allen Brooks

“Houston

Thirty-six years ago, Apollo 13 experienced an explosion on its way to the moon. The crew used its ingenuity and training to adjust their course and safely return to earth. In mid September we wrote about the critics of Peak Oil,

The email kicked off an exchange of views about the subject and what

I thought I would highlight the key points in Douglas Leyendecker’s email to me about his view of the need for

Mr. Leyendecker’s concern focuses on two issues: Global warming and our

Global warming, whether one believes the underlying science or not, has become a magnet for powerful and wealthy people seeking a cause for making the world a better place to live. The momentum behind this cause has accelerated over the past several years, helped by a spate of weather-related phenomena such as last year’s off-the-charts hurricane season.

While some might point to Al Gore’s movie, “An Inconvenient Truth,” as the catalyst for the global warming movement, we think the embracing of the issue by two powerful Republican politicians – Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger of California and Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York City, might better represent the tipping point marking an acceleration in the drive to commercialize disruptive energy technologies. Increasingly, more mainstream figures – politicians, businessmen and others – are embracing the need to attack and solve the global warming problem.

In deed, The New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman recently wrote about the results of polling conducted by campaign advisor James Carville, the originator of the

Once again,

Gov. Schwarzenegger’s statement may be a self-fulfilling prophecy. The venture capital industry, ensconced in Silicon Valley in the

In our September Musings article, we discussed the alternative and clean technology investment opportunities outlined by Rodrigo Prudencio of Nth Power LLC, in his presentation at the Rice Alliance conference. He listed the following clean technology investment opportunities:

· Transportation

Batteries not fuel cells; maybe drive-trains

· Fuels

Bio-engineering

· Energy Networks

Sensors, communications, data-management

· Distributive Energy

Alternative utilities; solar focus

· Materials and Nanotechnology

Key enablers that may be big winners

While this list probably does not contain every possible technology, the important thing to understand is that venture capitalists are experienced in seeking out, identifying and nurturing disruptive technologies that have the potential of creating meaningful new markets. The key question is when their efforts in alternative energy technologies may begin to bear fruit. Mr. Leyendecker believes that the 2010-2020 decade is when these disruptive technologies will alter the traditional hydrocarbon value proposition with potentially disastrous consequences for

Mr. Leyendecker has been searching for a better moniker than “clean tech” as he believes that title does not adequately explain the nature of the challenge for the hydrocarbon industry. For the time being, he believes “alternative energy technology” and/or “clean technology” should really be called “energy consumption conservation technologies.” Mr. Leyendecker believes that these disruptive technologies are a ticket to reduced hydrocarbon demand that will lower commodity prices. This ties to his second rationale for why alternative energy investing is here to stay. Less demand and lower oil prices would reduce the income flowing to Islamic-centric Middle East governments who have become the world’s principal oil suppliers and who have targeted the

We have become their enemy due to our hedonistic and social mores. In Mr. Leyendecker’s view, the problem arises because these people suffer from low self-esteem that comes from not having had to have worked to acquire their wealth. Theirs was an accident of location. God deposited much of the world’s oil resources under these Islamic radical countries. As the Muslim population in these

Since the Muslim God gave them their wealth, he must be the best God in the world. Yet with all that wealth, most of these countries have rampant poverty, underachieving societies and feeble economies. In contrast to these Middle East Muslim economies, consider the dynamic society and vibrant economy of

More and more, people are beginning to embrace the view known as “the curse of commodities.” The curse relates to the instant country wealth that comes from the raw materials buried there and not from the effort of citizens to create products or services that have value. The curse creates a distorted view of the value of one’s creative efforts and acts to undercut the development of a stable, progressive and tolerant society. A possible solution to the curse of commodities is to diminish a country’s income stream and wealth, and the way to do that in the

From Mr. Leyendecker’s viewpoint,

Will

Looking at the issue of disruptive technologies and hydrocarbon-based energy from a broader perspective, we are fascinated by the political battles waged over efforts to develop alternative energy projects, whether they are wind, solar or nuclear power sources. The battle over expanding the ethanol business, at least the corn- or sugar-based fuels, likely will become more intense as people question ethanol’s net-energy balance, whether the program is really a sop to the farm lobby and the morality of using foodstuffs for energy when there are starving people in the world.

We believe that real disruptive energy technologies will come from somewhere or something we are not aware of today. We always used to think that Star Trek’s mobility technology – “Beam Me Up, Scottie” – would prove the ultimate transportation system. Unfortunately, it seems to only work on television.

In thinking about disruptive energy technologies, how they develop and how they alter the status quo, we looked at the role of the horse in

Sanitary experts in the early part of the twentieth century agreed that the normal city horse produced between 15 pounds and 30 pounds of manure a day, with the average being about 22 pounds, plus about a quart of urine. Usually this waste was deposited along the route the workhorse traversed. (According to one report, mules were used in some cities because they could be “potty” trained as opposed to horses. Mules could be led to one location to defecate and another to urinate.) The volume of daily waste generated in each city created the need to hire street cleaners and crosswalk sweepers. In addition, it generated an opportunity to develop street cleaning machines. Interestingly, the street cleaners were largely alien workers, which reminds us of today’s debate about illegal immigrants and their willingness to work the low-paying and unpleasant jobs ordinary American citizens shun.

In

An additional problem for the cities was the disposal of dead horses and mules. Estimates were that the average streetcar horse had a life expectancy of two years. It was not uncommon for drivers to be seen beating their overworked nags, which prompted Henry Bergh to found the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1866. According to figures,

The solution to the horse waste problem was not to put diapers on the animals, or figure out how to potty-train them, rather it was to find some other energy source to perform the work that created fewer, or at least more manageable, pollution problems. The development of steam, electricity and gasoline power sources obviated the need for workhorses in cities. The driver behind the acceptance of these alternative power sources was health concerns, although economics also played a role. Sound familiar? To understand these changes, we are extracting two paragraphs about the shift from the essay, The Centrality of the Horse to the Nineteenth-Century American City, written by Dr. Joel Tarr of Carnegie University and Dr. Clay McShane of Northeastern University, and published in The Making of Urban America, (Raymond Mohl, ed.), NY: SR Publishers, 1997.

“Horses did not disappear from cities overnight. Rather, they went function by function. It has already been noted that, while horse-powered machines persisted in manufacturing until about 1850, they were largely replaced by other energy sources in the following decade. The next use of urban horses to disappear was pulling streetcars. Their demise was very rapid, as between 1888 and 1892 almost every street railway in the

“The coming of the automobile dealt another large blow to the horse. Experimental motor cars had been around for a long time, but cities had always banned them. The crisis of the 1890s and early twentieth century, involving public health fears about pollution, traffic jams, and rising prices for both hay, oats, and urban land, made municipal governments and urban residents much more ready to switch to autos. A number of articles in popular magazines repeated the argument by a writer in Munsey’s Magazine that "the horse has become unprofitable. He is too costly to buy and too costly to keep." The process of substitution went faster in the

The transition to the disruptive technology of mechanical power from the traditional and dominant horsepower had both positive and negative implications. Traffic jams and polluted air were a couple of the negatives. Vehicle-related deaths were another. Offsetting these negatives were the positive health benefits of reduced diseases, cleaner clothes and better air quality. For certain people, their livelihood was impacted negatively. In 1880,

Eni CEO Explains High World Oil Prices

In the October 7 New York Times, there was a brief interview with Paolo Scaroni, the chief executive of Eni SpA (E-NYSE), the international oil company headquartered in Italy. We thought his answer to the reporter’s question about high oil prices was both clear and insightful, but important it should be read as a message to American citizens.

“Q. Some people believe high oil prices are here to stay. Do you share that view?

“A. First of all prices are not very high. Sixty dollars a barrel is not very high. If they were high, the American consumer in particular would behave differently. As long as each American consumer burns 26 barrels of oil per year against 12 for Europeans, this means that the prices are not high. High means that people start to say that I can use my energy better. Today, a barrel of oil is worth half a barrel of Coca-Cola. So you should put things into perspective. It has been clear to everybody that the Western world can live with oil above $30, $40, $50, $60, $70 a barrel and economies expand, inflation is low, and consumers continue to drive S.U.V.’s and air-conditioners are so high in American restaurants that you have to put on a coat otherwise you get sick.”

Seems Like Old Times Again – Look Out!

Anyone who has been in or around the energy business for very long has to feel more comfortable given current events. Why? Because OPEC is reacting to the recent fall in oil prices with its customary approach, i.e., talking up a cut in its production. It is hard to believe that this situation happened only two years ago. At that time, OPEC’s announcement of a prospective cut in its production was greeted by crude oil traders with a rally that jumped oil prices 15% higher. This time, however, the talk has produced very little material price appreciation. Are other considerations at work?

Do investors and analysts remember the last time we experienced OPEC producing flat-out as oil demand fell? It was in late 1997. In the summer of that year,

The imbalance between oil supply and demand had been exacerbated further by the recently stepped-up OPEC production that was attempting to cool off the rise in crude oil prices driven by global demand growth – primarily due to Asian consumption. If you don’t remember what happened, here’s a brief refresher.

As the world’s economy recovered from the early 1990s recession, oil demand was growing. It increased 1.9% in 1994 and 1.7% in 1995, but projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA) called for demand to grow by 2.4% in 1996 and 2.7% in 1997. Crude oil prices that had traded in the upper teens for all of 1993 through 1995 jumped into the low $20s, averaging slightly over $22 for all of 1996. By December of 1996, crude oil was trading over $25 per barrel. Oil prices moderated some in the first half of 1997 and then fell below $20 during the summer before strengthening in the fall to yield an average oil price for 1997 of slightly over $20.

In December 1997, the IEA was projecting demand growth of 2.8% for the year, following on 1996’s 2.4% growth, and further growth in 1998 of 2.5%. The December IEA monthly talked about an additional 500,000 to 1.1 million b/d of OPEC production coming into the market. They also hinted at the first signs of concern about demand weakness. Between November and December of 1997 crude oil prices dropped almost $2 per barrel. In January 1998, they dropped another $1.50 per barrel, bringing them to an average for the month of $16.72. For the rest of 1997, crude oil prices weakened every month until hitting bottom in December at $11.35.

The December 1998 IEA monthly began with the headline: What Happened To Demand? The previous forecast for a 1.85 million b/d demand growth in 1998 had been pared to only 500,000 b/d. With revenue plummeting, OPEC members, lead by Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, began a dance with non-OPEC producers (

So will we have a repeat of 2004 or 1997? The answer to that question will determine whether oil prices are headed higher in the near-term or long-term. If it is the long-term scenario, then we are likely to have a period of rough sledding ahead for energy markets and energy stocks. In an attempt to answer that question, we looked at the global oil production picture and how it has changed between 1997 and August 2006. Global supply had increased by 11.44 million b/d, with OPEC, including its NGLs, accounting for over 4 million b/d of that total. Within OPEC, all producers are up except

Exhibit 1. Global Oil Supply Change by Region

Source: IEA; PPBH

On the losing side of the equation, North America is down due to falling

Are Venture Capital Pros’ Concerns True for Energy?

Sevin Rosen Funds, one of the oldest and most successful technology venture capital firms, is returning money raised from clients due to its perception that investment opportunities are not attractive. The firm was in the process of raising money for its Fund X when it decided to abort the process. The firm wrote a letter to its prospective investors who had ponied up commitments of between $250 million and $300 million. The firm wrote, “The venture environment has changed so that overall returns for the entire industry are way too low and even the upper quartile returns have dropped to insufficient levels.”

The problem, according to partners of Sevin Rosen who spoke to the media and financial press, is that too much money has gone to venture capital firms who are providing financing to too many companies in every conceivable sector of the industry. Too much capital is one problem, but the lack of attractive exit opportunities is potentially as severe. Sevin Rosen believes that the dearth of initial public offerings (IPOs) plus a current market for technology company acquisitions at valuations it considers too low will limit the fund’s ability to deliver the kind of returns that venture investors have come to expect. At the end of 2005, venture capitalists had a combined $261 billion under management. That is more money than at any time in the history of the industry.

Exhibit 2. Sevin Rosen’s Concern About Inadequate Returns

Source: NYT

Sevin Rosen’s decision, and the rationale behind it, presents an interesting backdrop for the current surge in energy private equity investing. Their decision is based not on where the market for IPOs and acquisitions are now, but where the Sevin Rosen partners think it will be five to seven years from now, the typical life of a venture fund. While the partners believe the markets are unlikely to change, other venture capitalists think differently. The big question is whether Sevin Rosen’s view is limited only to venture capital investing, as there has been a substantial volume of funds flowing into private equity funds, too.

Last spring we heard a partner from the private equity firm HM Capital Partners LLC discuss the change at his organization in light of the challenges for generating superior investment returns for their investors. His thesis was very similar to Sevin Rosen’s, but probably reflected a little more emphasis on the impact of current valuations (too high), due to so much new private equity money, that was limiting upside profit potential. He said that this changed environment was one reason why founder Tom Hicks was retiring from the firm. Private equity investors utilize the same exit strategies as venture capital investors, so if Sevin Rosen’s view about current and future financial markets reflecting weak valuations proves true for all industry sectors, then energy private equity investors should be concerned.

Since the spring run-up in energy stock prices, the market for energy-related IPOs has been extremely weak, resulting in a number of offerings being cancelled or delayed. One energy-related IPO underway is for Paradigm Ltd., a seismic-software and data processing company, which underwriters are attempting to market as a technology company. The problem with this strategy is that Paradigm’s customers are all energy companies, and there aren’t too many customers. That would seem to make it difficult to call it a technology company rather than an oil service company.

Energy-oriented private equity firms, who are scrambling to invest their huge sums of money in private companies should consider whether Sevin Rosen’s and HM Capital’s views have any merit. If they do, then private company valuations will likely plateau or decline. The valuation changes are needed in order to open up the prospective return potential for private equity investors. Lower valuations for private equity investors could open up opportunities for strategic buyers to become more active in the merger and acquisition market for private companies. That could set the stage for a wave of industry consolidation that might wind up paralleling a similar consolidation phase in the producer sector. If that happens, the face of the oil and gas and oilfield service industries would be altered dramatically.

For Energy Speculators: 2006 Hurricane Season a Bust

The Colorado State University Department of Atmospheric Science hurricane forecasting team has recently cut its forecast for storms this hurricane season due to the development of El Niño conditions in the

When the 2006 tropical storm forecasting season began last December, the

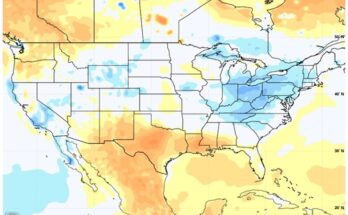

When one looks at a map showing the paths of the named tropical storms so far this year, it almost seems as though the U.S. mainland was about a quarter-turn to the left of the main track of the storms. The impact of this misplacement was to diminish the number of days that tropical storm conditions impacted the

Exhibit 3. 2006 Hurricanes Were Largely Irrelevant

Source: Weatherunderground.com

The expectation of a severe tropical storm/hurricane season this year was marked by an initial forecast in December 2005 for 17 named storms including nine hurricanes, of which five would be intense (Category 3 or better). That initial forecast was maintained until early in the hurricane season as weather conditions were consistent with the expectations on which the forecast was based. When Tropical Storm Alberto formed in early June, the forecasters were feeling comfortable with their forecasts and concerns about the impact on the

Exhibit 4. El Niño Formation Undercut Hurricane Forecast

Source: Colorado State Univ.; PPHB

As El Niño conditions strengthened, the expected severity of the hurricane season diminished. At the start of August,

The

Based on the new forecasting model and historical patterns,

The New Oil Sands Business Model?

On October 5, ConocoPhillips (COP-NYSE) and EnCana Corp. (ECA-NYSE) announced the creation of two new partnerships designed to facilitate the accelerated development of oil sands resources in northern

The upstream partnership, headquartered in

The downstream partnership, headquartered in

Several weeks ago, Murray Edwards, vice-chairman of Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. (CNQ-TSX), speaking to a Canadian business group, discussed the challenges to developing

Mr. Edwards questioned the impact of cost inflation on project economics and production goals. “Given the current challenges we face…it is going to be difficult for the Canadian sector to deliver the forecast growth in oil sands volumes over the next 15 years,” said Mr. Edwards in his speech. “Costs are accelerating to the point where you have to start wondering if projects are still economic.” According to Mr. Edwards, in the past five years, the price to build a

project has doubled. That trend seems to be intact, given Shell Canada Ltd.’s (SHC-TSX) declaration in July that a planned expansion of its existing oil sands project could cost C$12.8 billion, up 50% from an estimate made just one year ago.

With this partnership deal, ConocoPhillips secures a future stream of heavy oil feedstock for two of its refineries, sufficient to justify investment in upgrading their processing capacity. It also has the potential to expand that capacity further if the oil sands output is expanded. At the same time, EnCana gains access to refining assets that would have been prohibitively expensive to acquire on its own, and that provide security for its investment in expanding the production from its two oil sands projects. This looks like a win-win situation for both companies, assuming oil prices stay sufficiently high to justify the mining costs for extracting the bitumen resource. At the same time, as we wrote last issue, expansion of the pipeline capacity for moving bitumen from northern Alberta to the U.S. is moving forward, which is another key factor in the development of this North American market. We wonder if there will be more deals like the ConocoPhillips-EnCana venture.

Contact PPHB:

1900 St. James Place, Suite 125

Houston, Texas 77056

Main Tel: (713) 621-8100

Main Fax: (713) 621-8166

www.pphb.com

Parks Paton Hoepfl & Brown is an independent investment banking firm providing financial advisory services, including merger and acquisition and capital raising assistance, exclusively to clients in the energy service industry.